Applying Accessibility Guidelines to Your Site

How did we end up with so many accessibility guidelines and standards? Which guidelines and standards apply to your site? The following information will demystify accessibility guidelines and standards.

The History of Accessibility Guidelines

As explained earlier in this guidebook, accessibility laws have been enacted and updated since 1968. Here is a brief history of the guidelines for buildings, recreation facilities, and trails:

-

American National Standards Institute (ANSI)— 1969 to 1980. The first accessibility guidelines used by Federal agencies under the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA).

-

General Services Administration Accessibility Guidelines—1980 to 1984. The General Services Administration (GSA) developed its own set of guidelines for all buildings other than those of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Postal Service. Those agencies developed their own guidelines.

-

Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards (UFAS)— 1984 to 2006. These standards updated and expanded the GSA accessibility guidelines. The standards were adopted under ABA and applied to all federally funded facilities, unless there was a higher standard of accessibility for that type of structure required by other legal standards or guidelines.

-

Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG)—1991 to 2010. ADAAG explains how to apply the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 in the built environment. These guidelines apply to services provided by State and local governments, and public accommodations, such as motels and hotels.

-

Americans with Disabilities Act/Architectural Barrier Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADA/ABAAG) of 2004. Issued by the U.S. Access Board, these guidelines were developed as a merger and update of UFAS and ADAAG requirements. Chapters 1 and 2 contain application, administration, and scoping requirements. The 100 and 200 series apply only to those entities covered by ADA, (State and local government entities and private entities open to the public) and are NOT for Federal agency use. The F100 and F200 series apply only to facilities constructed by, for, or on behalf of Federal agencies. Chapters 3 through 10 provide the technical specifications that apply to all entities, unless the State or Federal agency has its own accessibility guidelines that are an equal or higher standard.

-

Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards (ABAAS) of 2006. The GSA, standard-setting agency for Forest Service facilities, adopted the ABA portion of ADA/ABAAG as the standard for all agencies under its standard-setting jurisdiction. The new ABAAS replaced UFAS.

-

ADA Standards for Accessible Design (ADASAD) of 2010. The U.S. Department of Justice adopted the ADA portion of ADA/ABAAG for use by State and local government entities and private entities open to the public. ADASAD is effective as of March 15, 2012.

-

Outdoor Developed Areas Accessibility Guidelines (ODAAG) of 2012. The U.S. Access Board developed ODAAG as a component of ADA/ABAAG. It contains accessibility guidelines for outdoor developed recreation areas and trails that are federally funded. Federal agencies may develop and use their own guidelines only if they are an equal or higher standard.

-

Forest Service Outdoor Recreation Accessibility Guidelines (FSORAG) and Forest Service Trail Accessibility Guidelines (FSTAG), 2012 Updates. These guidelines are an equal or higher standard than ODAAG for outdoor recreation facilities and trails on the National Forest System. These guidelines must be used for the design, construction, alteration, purchase, or replacement of recreation sites, facilities, constructed features, and trails that meet FSTAG criteria on the National Forest System (FSM 2330 and FSM 2350).

Current Accessibility Guidelines That Apply to the Forest Service

The Forest Service and those working with or for the Forest Service on National Forest System land must comply with the following enforceable guidelines and standards when designing, constructing, or altering any facility or component addressed by those standards on National Forest System land.

Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards (ABAAS). Forest Service drinking fountains, toilet facilities, parking lots and spaces, cabins, and administrative buildings are among the components covered by ABAAS. The complete ABAAS is available at http://www.access-board.gov/guidelines-and-standards/buildings-and-sites/about-the-aba-standards/aba-standards.

Forest Service Outdoor Recreation Accessibility Guidelines (FSORAG) and Forest Service Trail Accessibility Guidelines (FSTAG). These guidelines must be used for the design, construction, alteration, purchase, or replacement of recreation sites, facilities, constructed features, and trails on the National Forest System. The complete FSORAG and FSTAG are available at http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/accessibility/.

Table 1 shows examples of different facilities that are covered by ABAAS, FSORAG, and FSTAG.

Table 1—Accessibility guidelines quick guide (which accessibility guidelines apply where).

| ABAAS | FSORAG (Apply only within National Forest System boundaries) |

FSTAG (Apply only within National Forest System boundaries) |

|---|---|---|

| Buildings, Boating, and Fishing | Recreation Site Features | Hiker and Pedestrian Trails |

|

All Buildings, including:

Building components such as:

Boating and fishing facilities, including:

|

New or reconstructed:

|

Trails that are new or altered and

and

or

|

What if the Guidelines Appear To Conflict With Each Other?

It may appear that some accessibility guidelines conflict with other guidelines or codes, or with the realities of the outdoor environment. Railings must be high enough to protect visitors from a drop off, but railings that high might limit the viewing opportunity for a person using a wheelchair. Which requirement takes priority? Trash receptacles are supposed to be accessible so that everyone can use them, but then how do we keep bears out? Handpumps are vital to drawing water in campgrounds where the water system isn't pressurized, but operating the long handle of the traditional pump requires more force and a longer reach than allowed by accessibility provisions. Roads that have restrictions or closures to use by motorized vehicles may be open to foot travel, so how can a road be gated or bermed to keep out vehicles but still allow access by a person using a wheelchair? When you are faced with these types of situations, stop and think carefully about the issues. The solution always comes back to ensuring safety, abiding by the regulations, and doing so in a manner that includes the needs of all people.

Railings—Guardrails, Handrails, and Safety

Accessibility never supersedes the requirements for safety. This issue most commonly arises at overlook areas, on viewing structures, and in similar locations. For safety, the International Building Code (IBC), http://www.iccsafe.org, section 1003.2.12 contains requirements for guardrail height and the spacing of rails where there is a drop off of 30 inches or more. These requirements provide opportunities for creative design and for managers and designers to think seriously about the level of development that is appropriate for the setting. The creativity challenge is to provide safety when designing the railing or structure adjacent to the drop off, while maximizing viewing opportunities. Methods of solving this challenge are discussed in "Viewing Areas" of this guidebook.

Reconsidering the level of development at a site may be another way to balance safety and accessibility issues. It may not always be appropriate to provide paths and interpretive signs. When signs indicate a scenic viewpoint and a pathway begins at the parking lot, visitors are likely to stop, pile out of their vehicle, and head down that pathway, often with the children running ahead. Because of the high level of development at the entrance to the pathway, visitors expect that the viewpoint will have a similar high level of development, including safety features. Development should be consistent at both ends of the pathway.

If the area isn't developed, such as a waterfall in the forest with no signs or constructed trail to it, it may not be appropriate to develop a viewpoint. Some scenic areas should remain natural so that people have the opportunity of adventure and solitude. The safety and accessibility requirements only apply when constructed features are added to the setting.

While the accessibility guidelines for outdoor recreation areas do not require handrails at stairs, consider the safety of the people using the stairs and the setting when deciding whether handrails are appropriate. What is the expected amount of use? The determination must be made on a case-by case basis. For example, a handrail might not be necessary where there are a few regularly spaced stairs to an individual camping unit. However, handrails on stairs in a high-traffic recreation site may be important for safe use of the stairs. If the decision is made to install handrails at a recreation site, consider how the appearance of over development can be avoided while providing for safe use of the stairs. Choose materials carefully; determine how many railings will be provided based on safety considerations rather than convention, and so forth. When it is determined handrails are needed for safety at a specific site in an outdoor recreation area, use the technical requirements for handrails located in ABAAS, section 505.

Terminology Tip

What's the difference between a guardrail, a handrail, and a grab bar?

The following explanations of terms are based on the International Building Code and the Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards. Keep these explanations in mind and use them to communicate more effectively.

-

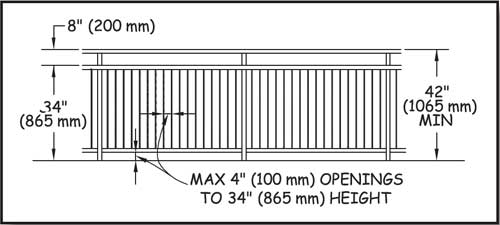

Guardrails protect people from dropoffs higher than 30 inches (760 millimeters). Guardrails must be at least 42 inches (1,065 millimeters) high. If the guardrail has openings that are less than 34 inches (865 millimeters) above the walking surface, they must be small enough to prevent a 4-inch (100-millimeter) sphere from passing through them (figure 15). Requirements for guardrails are detailed in the International Building Code, section 1003.2.12.

-

Handrails provide a steady support for persons who are going up or down stairs or inclines. Handrails must be between 34 inches (865 millimeters) and 38 inches (965 millimeters) above the walking surface and be easy to grip. Details about acceptable configurations for handrails are provided in the International Building Code, section 1003.3.3.11 and in the Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards, section 505.

-

Grab Bars provide stability and allow people to use their arms to help them move short distances. The most common location for grab bars is in restrooms. The required locations of grab bars are explained in the Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards, chapter 6. Details about grab bar configuration and attachment are provided in the Architectural Barriers Act Accessibility Standards, section 609 and in the International Building Code, chapter 11.

Figure 15— Dimensions required for guardrails.

Trash Receptacles and Wildlife

Safety is also the primary issue when it comes to the accessibility of trash receptacles. In bear country, use trash and recycling containers designed to keep the bears out to minimize contacts between bears and humans. Operating controls for these types of containers require more force than is allowed for accessible operation. Until bear-resistant trash and recycling containers that comply with the technical requirements for accessible operating controls are available from more than one source, recreation areas where bears and other large animals pose a risk to humans are exempt from this requirement. Incidentally, dumpsters—the big containers that are mechanically lifted and tipped to empty into commercial garbage trucks—are exempted from accessibility guidelines. More information about trash receptacles is in "Trash, Recycling, and Other Essential Containers" of this guidebook.

Handpumps and Water Systems

Handpumps also have been a concern (figure 16). Because of the piston-like pump mechanism, handpumps require a long reach. As the depth of the well increases, so does the force necessary to draw water, so most handpumps require a force greater than 5 pounds (2.2 newtons) to operate. An accessible handpump is now available for purchase. For shallower wells, this pump can draw the water while remaining in full compliance with the grasping, turning, and pressure restrictions of the accessibility guidelines (figure 17). More information about the new pump is available at http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation/programs/accessibility/. For wells with a static water depth of 40 feet (12 meters) or less, the accessible handpump can be used for many new or replacement installations. Accessible pumps for deeper wells are being developed and should be used when they become available. In the meantime, the accessibility requirements for handpump operating controls are under an exception explained in "Water Hydrants" of this guidebook.

Figure 16—Not all campers can operate a standard handpump.

Figure 17—With an accessible handpump, the choice of who does the pumping is up to the campers.

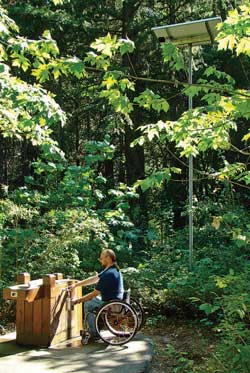

Solar powered water systems (figures 18 and 19) are an excellent sustainable solution that can provide drinking water throughout the recreation season. In addition, a faucet that fully complies with the accessible operating control requirements can be used (figure 20). Even national forests in Northern States are having good success with their solar systems.

Figure 18—The water pump inside the pumphouse at Vermilion Falls Recreation Area on the Superior National Forest is powered by the solar panels on the roof. People can obtain drinking water without using a handpump at this site that has no electric service.

Figure 19—The water pumps for many campgrounds, such as this campground in the deep, narrow Icicle River Valley of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest, can be housed in small pedestal enclosures and powered by solar panels on an adjacent pole. The pedestal enclosure also houses solar batteries.

Figure 20—This water spigot is operated by first pushing the handle to one side, then pressing the push button. The water will stop when the button is no longer depressed.

Foot Travel on Trails and Roads With Restrictions

When gates, barriers, or berms are installed on a trail or a road to close it to motorized traffic or for other purposes, but foot travel is encouraged beyond the closure, people who use wheelchairs that meet the legal definition must be able to get behind the closure, as required by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. As explained in "Program Accessibility" of this guidebook, a wheelchair is permitted anywhere foot travel is permitted.

When foot travel is encouraged beyond a closure, the Office of General Counsel of the U.S. Department of Agriculture has determined that a minimum of 36 inches (915 millimeters) of clear passage must normally be provided around or through the gate, berm, or other restrictive device (figures 21 and 22) to ensure that a person who uses a wheelchair can participate in the opportunity behind the restriction. This clear passage is required by the accessibility guidelines as explained in "Gates and Barriers" of this guidebook. Various methods can provide pedestrian passage around a restrictive device, but prevent passage by animals or vehicles that are not allowed beyond the gate or barrier. The Forest Service has developed designs for the tech tip "Accessible Gates for Trails and Roads." These gate designs can be locally constructed from materials appropriate to the setting. The plans are available at http://www.fs.fed.us/recreation /programs/accessibility/pubs/htmlpubs/htm06232340/index.htm and http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/fspubs/.

Figure 21—This road closure gate does not provide enough clearance to allow pedestrian passage.

Figure 22—One way to get around a vehicle road closure gate: a paved bypass.

Indications that foot travel is encouraged include:

-

Destination signing

-

A pedestrian recreation symbol without a slash

-

A Forest Service map that highlights an opportunity behind the closure

-

A trail management objective or road management objective stating that pedestrian use is encouraged

In areas where foot travel isn't encouraged, but occasional pedestrian use is allowed before and after installation of the restriction device, work with individuals who use wheelchairs to determine the best solution.

User Comments/Questions

Add Comment/Question