ADA Best Practices Tool Kit for State and Local Governments

On December 5, 2006, February 27, 2007, May 7, 2007, and July 26, 2007, the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice issued installments of a new technical assistance document designed to assist state and local officials to improve compliance with Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in their programs, services, activities, and facilities. The new technical assistance document, which will be released in several installments over the next ten months, is entitled “The ADA Best Practices Tool Kit for State and Local Governments.”

The Tool Kit is designed to teach state and local government officials how to identify and fix problems that prevent people with disabilities from gaining equal access to state and local government programs, services, and activities. It will also teach state and local officials how to conduct accessibility surveys of their buildings and facilities to identify and remove architectural barriers to access.

The first and second installments of the ADA Tool Kit, issued December 5, 2006, include:

About This Tool Kit (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 1, ADA Basics: Statutes and Regulations (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 2, ADA Coordinator: Notice and Grievance Procedure (HTML) | (PDF)

The third and fourth installments, issued February 27, 2007, include:

Chapter 3, General Effective Communication Requirements Under Title II of the ADA (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 3, Addendum: Title II Checklist (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 4, 9-1-1 and Emergency Communications Services (HTML) | (PDF)

The fifth and sixth installments, issued May 7, 2007, include:

Chapter 5, Website Accessibility Under Title II of the ADA (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 5, Addendum: Title II Checklist (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 6, Curb Ramps and Pedestrian Crossings (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 6, Addendum: Title II Checklist (HTML) | (PDF)

The seventh installment of the Tool Kit, issued July 26, 2007, includes:

Chapter 7, Emergency Management under Title II of the ADA (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 7, Addendum 1: Title II Checklist (Emergency Management) (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 7, Addendum 2:The ADA and Emergency Shelters: Access for All in Emergencies and Disasters (HTML) | (PDF)

Chapter 7, Addendum 3: ADA Checklist for Emergency Shelters (HTML) | (PDF)

Introduction to Appendices 1 and 2 (HTML) | (PDF)

While state and local governments are not required to use the ADA Best Practices Tool Kit, the Department encourages its use as one effective means of complying with the requirements of Title II of the ADA.

About This Tool Kit

Give a person a fish, and you provide food for a day. Teach a person to fish, and you provide food for a lifetime.

-- Chinese Proverb

During the past five years, the Civil Rights Division of the United States Department of Justice has worked with communities across the United States to improve access to state and local government for over 3 million people with disabilities.

We found that, despite good intentions, many communities did not have the knowledge or skills needed to identify barriers to access in their programs, activities, services, and facilities. They did not know how to survey buildings to identify physical barriers. They did not know how to review programs and policies for compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”). They asked us to help fill their knowledge gap.

The Civil Rights Division is assembling this Tool Kit to help communities better understand the issues involved in providing equal access for people with disabilities. We encourage state and local government officials to use this Tool Kit to learn:

-

how to survey facilities and identify common architectural barriers for people with disabilities;

-

how to identify red flags indicating that their programs, services, activities, and facilities may have common ADA compliance problems; and

-

how to remove the barriers and fix common ADA compliance problems they identify.

Are state and local governments required to use this Tool Kit? No. But they are required to comply with the requirements of Title II of the ADA, which prohibits state and local governments from discriminating on the basis of disability. This Tool Kit will provide a reasonable approach to help communities achieve compliance.

The Tool Kit will be released in installments to help state and local officials begin to set up an “accessibility audit.” This first two installments of the Tool Kit include:

-

Chapter 1, ADA Basics (HTML) | PDF:

Statute and Regulations. -

Chapter 2, ADA Coordinator, Notice & Grievance Procedure (HTML) | PDF:

Administrative Requirements Under Title II of the ADA. Chapter 2 includes a checklist that will help state and local officials determine if their governments are in compliance with basic ADA administrative requirements. It also includes a sample “ADA Notice” and a sample “ADA Grievance Policy” that state and local officials can use to comply with basic ADA administrative requirements. -

Chapter 3, General Effective Communication Requirements Under Title II of the ADA (HTML) | PDF:

Chapter 3 explains what it means for communication to be “effective,” which auxiliary aids and services can potentially provide effective communication,and when those auxiliary aids and services must be provided. It also includes a checklist (PDF) to help state and local officials assess compliance with the ADA’s general effective communication requirements. -

Chapter 4, 9-1-1 and Emergency Communications Services (HTML) | PDF:

Chapter 4 explains how the ADA’s effective communication requirements apply to 9-1-1 and emergency communications services. The chapter also includes a checklist (PDF) that state and local officials can use to identify common problems with the accessibility of their 9-1-1 and emergency communications services. -

Chapter 5, Website Accessibility (HTML) | PDF

Chapter 5 explains how Title II of the ADA applies to state and local government websites, describes technologies people with disabilities use to access the Internet, discusses website design practices that pose barriers to people with disabilities, and identifies solutions that can eliminate these online barriers. The Chapter also includes a checklist (PDF) that can be used by state and local governments to review their website policies and assess the accessibility of their websites. -

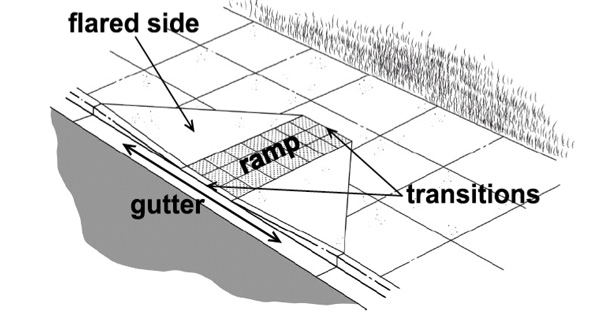

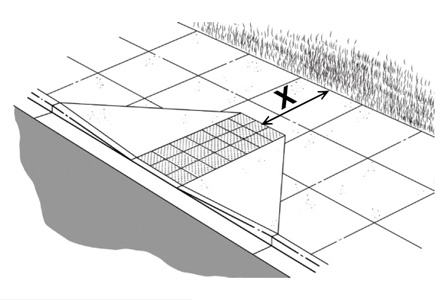

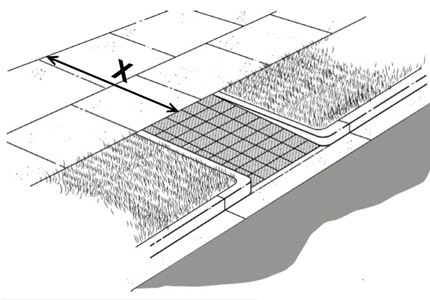

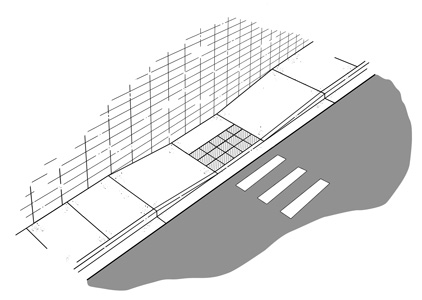

Chapter 6, Curb Ramps and Pedestrian Crossings (HTML) | PDF

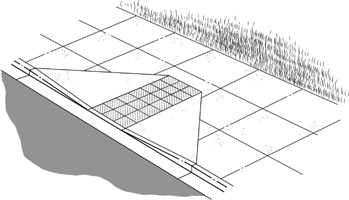

Chapter 6 explains Title II’s requirements for providing curb ramps at pedestrian crossings, lists some key characteristics of accessible curb ramps, and discusses where and when state and local governments must provide accessible curb ramps. The Chapter outlines the steps you can take to ensure that your state or local government is complying with Title II’s requirements for accessible curb ramps and includes a checklist (PDF)your entity can use to assess your compliance. The next installment of the Tool Kit will include a survey form and survey instructions you can use to determine if curb ramps are accessible.

Watch for future installments of the Tool Kit, which will further guide communities in understanding how to review the accessibility of state and local government programs, services, and activities, and how to survey buildings and facilities to identify barriers to access for people with disabilities.

Note: This Tool Kit provides an overview of ADA compliance issues for state and local governments. While comprehensive, it does not address every possible ADA compliance issue. The Tool Kit should be considered a helpful supplement to – not a replacement for – the regulations and technical assistance materials that provide more extensive discussions of ADA requirements. It also does not replace the professional advice or guidance that an architect or attorney knowledgeable in ADA requirements can provide.

A. Introduction

On July 26, 1990, President George H. W. Bush signed into law the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”) saying these words, “Let the shameful wall of exclusion finally come tumbling down.”1 One of the most important civil rights law to be enacted since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the ADA prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities.

What does the ADA mean for state and local governments in the delivery of their programs, services, and activities, as well as their employment practices? In the broadest sense, it requires that state and local governments be accessible to people with disabilities.

Accessibility is not just physical access, such as adding a ramp where steps exist. Accessibility is much more, and it requires looking at how programs, services, and activities are delivered. Are there policies or procedures that prevent someone with a disability from participating (such as a rule that says “no animals allowed,” which excludes blind people who use guide dogs)? Are there any eligibility requirements that tend to screen out people with disabilities (such as requiring people to show or have a driver’s license when driving is not required)?

Before you begin your accessibility audit, you need to understand the answers to several basic questions.

-

What is the ADA, and are there any other laws or regulations I need to know about to do an accessibility evaluation?

-

What is a “disability” under the ADA, and is having one enough to be covered by the ADA?

-

What types of barriers are there to accessibility?

-

What are states’ and local governments’ obligations under the ADA?

1 Speech of President George H.W. Bush at the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, reprinted at http://www.eeoc.gov/ada/bushspeech.html.

B. The Legal Landscape

Before looking at the individual parts of the ADA, it’s best to look at the whole picture. Having an overview of the laws, regulations, and other legal requirements helps to put everything in context.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Broader than any disability law that came before it, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act made it illegal for the federal government, federal contractors, and any entity receiving federal financial assistance to discriminate on the basis of disability.2 Section 504 obligates state and local governments to ensure that persons with disabilities have equal access to any programs, services, or activities receiving federal financial assistance. Covered entities also are required to ensure that their employment practices do not discriminate on the basis of disability.

2 Rehabilitation Act of 1973 § 104, 29 U.S.C. § 794 (2006).

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

The ADA is built upon the foundation laid by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. It uses as its model Section 504's definition of disability and then goes further. While Section 504 applies only to entities receiving federal financial assistance, the ADA covers all state and local governments, including those that receive no federal financial assistance. The ADA also applies to private businesses that meet the ADA’s definition of “public accommodation” (restaurants, hotels, movie theaters, and doctors’ offices are just a few examples), commercial facilities (such as office buildings, factories, and warehouses), and many private employers.

While the ADA has five separate titles, Title II is the section specifically applicable to “public entities” (state and local governments) and the programs, services, and activities they deliver. The Department of Justice (“DOJ” or the “Department”), through its Civil Rights Division, is the key agency responsible for enforcing Title II and for coordinating other federal agencies’ enforcement activities under Title II.

In addition, the Department has the ability to enforce the employment provisions of Title I of the ADA as they pertain to state and local government employees. DOJ is the only federal entity with the authority to initiate ADA litigation against state and local governments for employment violations under Title I of the ADA and for all violations under Title II of the ADA.

Some Helpful Tools

The Department’s Title II regulations for state and local governments are found at Title 28, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 35 (abbreviated as 28 CFR pt. 35. The ADA Standards for Accessible Design are located in Appendix A of Title 28, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 36 (abbreviated as 28 CFR pt. 36 app. A). Those regulations, the statute, and many helpful technical assistance documents are located on the ADA Home Page at www.ada.gov and on the ADA technical assistance CD-ROM available without cost from the toll-free ADA Information Line at 1-800-514-0301 (voice) and 1-800-514-0383 (TTY).

The ADA Standards for Accessible Design (the ADA Standards)

The ADA Standards for Accessible Design, or the “ADA Standards,” refer to the requirements necessary to make a building or other facility architecturally (physically) accessible to people with disabilities. The ADA Standards identify what features need to be accessible, set forth the number of those features that need to be made accessible, and then provide the specific measurements, dimensions and other technical information needed to make the feature accessible.

Caution: You may hear the acronym ADAAG used to refer to the ADA Standards. ADAAG stands for the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines, which are issued by the United States Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (called the “Access Board” for short). ADAAG is not the same as the ADA Standards. The Department’s regulations must be consistent with the ADAAG, but the ADAAG contains guidelines, not enforceable standards.

Uniform Federal Accessibility Guidelines (UFAS)

These are the architectural standards originally developed for facilities covered by the Architectural Barriers Act, a law that applies to buildings designed, built, altered or leased by the federal government. They also are used to satisfy compliance in new or altered construction under Section 504. State and local governments have the option to use UFAS or the ADA Standards to meet their obligations under Title II of the ADA. However, if states and local governments choose to use the ADA Standards, the elevator exemption contained in the ADA Standards may not be used 3. Also, only one set of standards may be used for any particular building. In other words, you cannot pick and choose between UFAS and the ADA Standards as you design or alter a building. DOJ also uses UFAS for certain special-use facilities when the ADA Standards have no scoping or technical provisions, such as for prisons and jails. A downloadable copy of UFAS can be found at http://www.access-board.gov/ufas/ufas.pdf and a searchable copy can be found at http://www.access-board.gov/ufas/ufas-html/ufas.htm. Technical assistance on UFAS is available from the U.S. Access Board at 1-800-872-2253 (voice) or 1-800-993-2822 (TTY) or TA@access-board.gov.

Did You Know? When discussing architectural standards, two terms are often used: “scoping” and “technical provisions.”

“Scoping” tells you where and how many accessible elements or features are required under the ADA Standards. “Technical provisions” give you the components, dimensions and installation details of the accessible elements.

For Example. Section 4.1.3(7) of the ADA Standards tells you generally about doors in new construction. There are four different scoping requirements that tell you the percentage or absolute number of which of the following types of doors must be accessible: doors going into a building, doors within a building, doors that are part of an accessible route, and doors as part of egress (i.e., exits for fire and life-safety purposes). Section 4.13 of the ADA Standards tells you the technical provisions for doors that are specific requirements, such as the required clear passage width of a doorway.

3 The elevator exemption, which only applies to non-governmental entities, states that elevators are not required in certain specified facilities. 28 C.F.R. pt. 36 app. A § 4.1.3(5).

C. ADA Fundamentals

The cornerstone of Title II of the ADA is this: no qualified person with a disability may be excluded from participating in, or denied the benefits of, the programs, services, and activities provided by state and local governments because of a disability.4 One simple sentence, but it has many words, phrases and ideas to understand.

4 42 U.S.C. § 12132; 42 U.S.C. § 12102(2)(B) & (C).

1. Who is Covered?

Not everyone is covered under the ADA. There are certain basic requirements that must be met in order to be protected. The first and most obvious requirement is that a person must have a disability.

a. Disability Defined

The ADA defines disability as a mental or physical impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.5 ADA protection extends not only to individuals who currently have a disability, but to those with a record of a mental or physical impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities, or who are perceived or regarded as having a mental or physical impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.6

Three things to ask yourself when determining whether an individual has a disability for purposes of the ADA are:

5 42 U.S.C. § 12202(2)(A).

6 42 U.S.C. § 12102(2)(B) & (C).

One: Does the individual have an impairment?

A physical impairment is a physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement or anatomical loss impacting one or more body systems.7 Examples of body systems include neurological, musculoskeletal (the system of muscles and bones), respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, lymphatic and endocrine.8

A mental impairment is a mental or psychological disorder.9 Examples include mental retardation, emotional or mental illness, and organic brain syndrome.10

The Department’s regulations also list other impairments, including contagious and noncontagious diseases; orthopedic, vision, speech and hearing impairments; cerebral palsy; epilepsy; muscular dystrophy; multiple sclerosis; cancer; heart disease; diabetes; specific learning disabilities; HIV disease (with or without symptoms), tuberculosis, drug addiction, and alcoholism.11

7 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(1)(i)(A).

8 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(1)(i)(A).

9 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(1)(i)(B).

10 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(1)(i)(B).

11 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(1)(ii).

Two: Does the impairment limit any major life activities?

An impairment cannot be a disability unless it limits something, and that something is one or more major life activities. A major life activity is an activity that is central to daily life.12 According to the Department’s regulations, major life activities include walking, seeing, hearing, breathing, caring for oneself, sitting, standing, lifting, learning, thinking, working,13 and performing manual tasks that are central to daily life.14 The Supreme Court has also decided that reproduction is a major life activity.15 This is not a complete list. Other activities may also qualify, but they need to be activities that are important to most people’s lives.

12 Toyota Motor Mfg., Kentucky, Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184 (2002).

13 Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624, 638-49 (1999). The Supreme Court has questioned whether “working” is a major life activity. However, “working” is identified as a major life activity under the regulation for Title II of the ADA, 28 C.F.R. § 35.104, and the regulation for Title I of the ADA, 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(I).

14 Toyota, 534 U.S. 184.

15 Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624 (1988).

Three: Is the limitation on any major life activity substantial?

Not only must a person have an impairment that limits one or more major life activities, but the limitation of at least one major life activity must be “substantial.” An impairment “substantially limits” a major life activity if the person cannot perform a major life activity the way an average person in the general population can, or is significantly restricted in the condition, manner or duration of doing so. An impairment is “substantially limiting” under the ADA if the limitation is “severe,” “significant,” “considerable," or "to a large degree."16 The ADA protects people with serious, long-term conditions. It does not protect people with minor, short-term conditions.

Here are some things to think about when trying to decide if an impairment is substantially limiting:

-

What kind of impairment is involved?

-

How severe is it?

-

How long will the impairment last, or how long is it expected to last?

-

What is the impact of the impairment?

-

How do mitigating measures, such as eyeglasses and blood pressure medication, impact the impairment? The Supreme Court has ruled that, if an impairment does not substantially limit one or more major life activities because of a mitigating measure an individual is using, the impairment may not qualify as a disability.17 Remember, however, that mitigating measures such as blood pressure medication may sometimes impose limitations on major life activities, and those must be considered as well.

16 Toyota, 534 U.S. 184.

17 Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471 (1999).

Example: Broken Arm – Under ordinary circumstances, a person with a broken arm is not covered by the ADA. Although a broken arm is an impairment, it is usually temporary and of short duration. Consequently, a broken arm is not considered to be substantially limiting is most circumstances.

Does a person with depression have a disability under the ADA?

You might think the answer would be “no” because depression does not seem to substantially limit any specific major life activity. However, someone who has had major depression for more than a few months may be intensely sad and socially withdrawn, have developed serious insomnia, and have severe problems concentrating. This person has an impairment (major depression) that significantly restricts his ability to interact with others, sleep, and concentrate. The effects of this impairment are severe and have lasted long enough to be substantially limiting.

b. A Qualified Person with a Disability

Having an impairment that substantially limits a major life activity may mean that a person has a disability, but that alone still does not mean that individual is entitled to protection under the ADA. A person with a disability must also qualify for protection under the ADA. A “qualified individual with a disability” is someone who meets the essential eligibility requirements for a program, service or activity with or without (1) reasonable modifications to rules, policies, or procedures; (2) removal of physical and communication barriers; and (3) providing auxiliary aids or services for effective communications.18

Essential eligibility requirements can include minimum age limits or height requirements (such as the age at which a person can first legally drive a car or height requirements to ride a particular roller coaster at a county fair). Because there are so many different situations, it is hard to define this term other than by examples. In some cases, the only essential eligibility requirement may be the desire to participate in the program, service, or activity.

What happens if an individual with a disability does not meet the eligibility requirements? In that case, you will have to look further to determine if the person with the disability is entitled to protection under the ADA. When a person with a disability is not qualified to participate or enjoy a program, service, or activity under Title II, there may be ways to enable the individual to participate, including, for example:

-

Making a reasonable modification to the rule, policy, or procedure that is preventing the individual from meeting the requirements,

-

Providing effective communication by providing auxiliary aids or services, or

-

Removing any architectural barriers.

18 28 C.F.R. § 35.105

Public entities must reasonably modify their rules, policies, and procedures to avoid discriminating against people with disabilities.19 Requiring a driver’s license as proof of identity is a policy that would be discriminatory since there are individuals whose disability makes it impossible for them to obtain a driver’s license. In that case it would be a reasonable modification to accept another type of government-issued I.D. card as proof of identification.

Examples of Reasonable Modifications

-

Granting a zoning variance to allow a ramp to be built inside a set-back.

-

Permitting a personal attendant to help a person with a disability to use a public restroom designated for the opposite gender.

-

Permitting a service animal in a place where animals are typically not allowed, such as a cafeteria or a courtroom.

Are there times when a modification to rules, policies and procedures would not be required? Yes, when providing the modification would fundamentally alter the nature of the program, service, or activity.

A fundamental alteration is a change to such a degree that the original program, service, or activity is no longer the same. For example, a city sponsors college-level classes that may be used toward a college degree. To be eligible to enroll, an individual must have either a high school diploma or a General Educational Development certificate (“G.E.D”). If someone lacks a diploma or G.E.D. because of a cognitive disability, would the city have to modify the policy of requiring a high school diploma or G.E.D.? Probably not. Modifying the rule would change the class from college level to something less than college level and would fundamentally alter the original nature of the class.

19 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(7).

People with disabilities cannot participate in government-sponsored programs, services, or activities if they cannot understand what is being communicated. What good would it do for a deaf person to attend a city council meeting to hear the debate on a proposed law if there was no qualified sign language interpreter or real-time captioning (that is, a caption of what is being said immediately after the person says it)? The same result occurs when a blind patron attempts to access the internet on a computer at a county’s public library when the computer is not equipped with screen reader or text enlargement software. Providing effective communication means offering auxiliary aids and services to enable someone with a disability to participate in the program, service, or activity.

Types of Auxiliary Aids and Services

There are a variety of auxiliary aids and services. Here are a few examples.

-

For individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing: qualified sign-language and oral interpreters, note takers, computer-aided transcription services, written materials, telephone headset amplifiers, assistive listening systems, telephones compatible with hearing aids, open and closed captioning, videotext displays, and TTYs (teletypewriters).

-

For individuals with who are blind or have low vision: qualified readers, taped texts, Braille materials, large print materials, materials in electronic format on compact discs or in emails, and audio recordings.

-

For individuals with speech impairments: TTYs, computer stations, speech synthesizers, and communications boards.

Persons with disabilities should have the opportunity to request an auxiliary aid, and you should give ‘primary consideration’ to the aid requested. Primary consideration means that the aid requested should be supplied unless: (1) you can show that there is an equally effective way to communicate; or (2) the aid requested would fundamentally alter the nature of the program, service, or activity.

Example: A person who became deaf late in life is not fluent in sign language. To participate in her defense of criminal charges, she requests real time computer-aided transcription services. Instead, the court provides a qualified sign language interpreter. Is this effective? No. Providing a sign language interpreter to someone who does not use sign language is not effective communication.

The Cost of Doing Business

The expense of making a program, service, or activity accessible or providing a reasonable modification or auxiliary aid may not be charged to a person with a disability requesting the accommodation.20

Example: What if a person asks for a sign language interpreter at a city council meeting? The cost may not be passed along to the person requesting that accommodation.

20 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(f).

Examples of Barriers to Accessibility

Architectural

-

A building has just one entrance that is up a flight of stairs and has no ramp.

-

The door to the only public restroom in a building is 28 inches wide.

Policies and Procedures

-

Requiring a driver’s license to obtain a library card from the public library.

-

A “No Animals” rule (without an exception for service animals) to enter a pie baking booth at a county fair.

Effective Communication

-

No assistive listening system for public meetings by a City Council.

-

A state’s website that cannot be accessed by blind people using screen reader software or those with low vision using text enlargement software.

A Final Word: Every disability is a disability of one. While some people with a particular disability may not be able to perform a certain task or participate in a particular program, service, or activity, others may be able to do so.

Example: Some people with severely impaired vision can drive safely so long as they use specially prescribed optical aids.

One Man’s Ability – and Disability

Jim Abbott played professional baseball. He was the 15th player to ever debut in the major leagues (and never play in the minor leagues) and had a 3.92 earned run average in his rookie year. Jim Abbott was born with one hand. If his home town had applied a blanket requirement that all little league players must have two hands, Jim Abbott might not have had the chance to develop into the professional athlete that he became.

The key to making correct decisions is an individualized assessment. Avoid blanket exclusions, and evaluate each person based on his or her own abilities.

Programs, Services, and Activities

Public entities may provide a wide range of programs, services, and activities. Police, fire, corrections, and courts are services offered by public entities. Administrative duties such as tax assessment or tax collection are services. Places people go such as parks, polling places, stadiums, and sidewalks are covered. These are just some examples (and by no means a complete list) of the types of programs, services, and activities typically offered by state and local governments.

Integrated Setting

One of the main goals of the ADA is to provide people with disabilities the opportunity to participate in the mainstream of American society. Commonly known as the “integration mandate,” public entities must make their programs, services, and activities accessible to qualified people with disabilities in the most integrated way appropriate to their needs.21

Separate or special activities are permitted under Title II of the ADA to ensure that people with disabilities receive an equal opportunity to benefit from your government’s programs, services, or activities.22 However, even if a separate program is offered to people with disabilities or people with one kind of disability, a public entity cannot deny a person with a disability access to the regular program. Under the ADA, people with disabilities get to decide which program they want to participate in, even if the public entity does not think the individual will benefit from the regular program.23

Example: A county may run a summer program for kids with disabilities in June and kids without disabilities in July. The county must allow kids with disabilities to attend either session.

21 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(d).

22 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(1)(iv).

23 28 C.F.R. § 35.130(b)(2).

3. When Was it Built? Why Does it Matter?

The ADA treats facilities that were built before it went into effect differently from those built or renovated afterwards. The key date to remember is January 26, 1992, when Title II’s accessability [sic] requirements for new construction and alterations took effect.24

24 28 C.F.R. § 35.151.

Before January 26, 1992

Facilities built before January 26, 1992, are referred to as “pre-ADA” facilities.25 If there is an architectural barrier to accessibility in a pre-ADA facility, you may remove the barrier using the ADA Standards for Accessible Design or UFAS as a guide, or you may choose to make the program, service, or activity located in the building accessible by providing “program access.”26 Program access allows you to move the program to an accessible location, or use some way other than making all architectural changes to make the program, service, or activity readily accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities.

Example: A small town with few public buildings operates a museum featuring the history of the area. The museum is in a two story building built in 1970, which has no elevator. The town may either install an elevator or find other ways to make the exhibits accessible to people with mobility disabilities. One program access solution in this case might be to make a video of the second floor exhibits for people to watch on the first floor.

There are many ways to make a program, service, or activity accessible other than through architectural modifications. Keep in mind, however, that sometimes making architectural changes is the best solution financially or administratively, or because it furthers the ADA’s goal of integration.

After January 26, 1992

Any facility built or altered after January 26, 1992, must be “readily accessible to and usable by” persons with disabilities.27 For ADA compliance purposes, any facility where construction commenced after January 26, 1992 is considered “new,” “newly constructed,” or “post-ADA.” “Readily accessible to and usable by” means that the new or altered building must be built in strict compliance with either the ADA Standards for Accessible Design or UFAS.

Altering (renovating) a building means making a change in the usability of the altered item. Examples of changes in usability include: changing a low pile carpet to a thick pile carpet, moving walls, installing new toilets, or adding more parking spaces to a parking lot. Any state or local government facility that was altered after January 26,1992 was required to be altered in compliance with the ADA Standards or UFAS.

When part of a building has been altered, the alterations must be made in strict compliance with architectural standards, including creating an accessible path of travel to the altered area.

Example: A county renovates a section of an administrative building. That renovated section must be altered in compliance with the ADA Standards or UFAS. In addition, the route from the accessible entrance of the building to the renovated section must be made accessible to people with disabilities. Features along the route, such as toilet rooms and water fountains, need to be made accessible as well.

Of course, it is possible for a pre-ADA building (i.e., built before 1992) to have altered elements. In that case, the public entity can provide program access for the programs housed in the non-altered portion of the building by making them available in the parts of the building that have been altered.

New and altered facilities must be built in compliance with the ADA Standards or UFAS regardless of what, if any, programs are located in them. Even if new or altered facilities are not open to the public, they must be accessible to people with disabilities.

27 28 C.F.R. § 35.151.

4. Enforcement and Remedies

An individual or a specific class of individuals or their representative alleging discrimination on the basis of disability by a state or local government may either file –

(1) an administrative complaint with the Department of Justice or another appropriate federal agency; or

(2) a lawsuit in federal district court.

If an individual files an administrative complaint, the Department of Justice or another federal agency may investigate the allegations of discrimination. Should the agency conclude that the public entity violated Title II of the ADA, it will attempt to negotiate a settlement with the public entity to remedy the violations. If settlement efforts fail, the agency that investigated the complaint may pursue administrative relief or refer the matter to the Department of Justice. The Department of Justice will determine whether to file a lawsuit against a public entity to enforce Title II of the ADA.

Potential remedies (both for negotiated settlements with the Department of Justice and court-ordered settlements when the Department of Justice files a lawsuit) include:

-

injunctive relief to enforce the ADA (such as requiring that a public entity make modifications so a building is in full compliance with the ADA Standards for Accessible Design or requiring that a public entity modify or make exceptions to a policy);

-

compensatory damages for victims; and/or

-

back pay in cases of employment discrimination by state or local governments.

In cases where there is federal funding, fund termination is also an enforcement option that federal agencies may pursue.

Chapter 2 ADA Coordinator, Notice & Grievance Procedure: Administrative Requirements Under Title II of the ADA

In this section, you will learn about the administrative requirements of Title II of the ADA, including the mandates to designate an ADA coordinator, give notice about the ADA’s requirements, and establish a grievance procedure. Questions answered include:

-

If the local government has fewer than 50 employees, do different requirements apply?

-

What are the responsibilities of an ADA Coordinator?

-

What are the benefits of having an ADA Coordinator?

-

What are the requirements for providing notice of the ADA’s provisions?

-

How and where must you provide ADA notices?

-

What is a grievance procedure?

-

What must an ADA grievance procedure include?

A. Designating an ADA Coordinator

If a public entity has 50 or more employees, it is required to designate at least one responsible employee to coordinate ADA compliance.1 A government entity may elect to have more than one ADA Coordinator. Although the law does not refer to this person as an “ADA Coordinator,” this term is commonly used in state and local governments across the country and will be used in this chapter.

The ADA Coordinator is responsible for coordinating the efforts of the government entity to comply with Title II and investigating any complaints that the entity has violated Title II. The name, office address, and telephone number of the ADA Coordinator must be provided to interested persons.

Common Question: Which employees count?

If a local government or other public entity has fewer than 50 employees, it is not required to appoint an ADA Coordinator or establish grievance procedures.

The number of employees is based on a government-wide total, including employees of each department, division, or other sub-unit. Both part-time and full-time employees count. Contractors are not counted as employees for determining the number of employees.

For example: Jones City has 30 full-time employees and 20 part-time employees. The employees include ten police department employees and eight fire department employees.

Jones City must have an ADA Coordinator and an ADA grievance procedure. The total number of employees is 50 because both full-time and part-time employees are counted. In addition, the police and fire departments are part of the city-wide employment pool, and the requirements for an ADA Coordinator and an ADA grievance procedure cover both of those departments.

1 Department of Justice Nondiscrimination on the Basis of State and Local Government Services Regulations, 28 C.F.R. pt. 35, § 35.107(a) (2005). See www.ada.gov/reg2.htm for the complete text of the Department of Justice’s Title II regulation.

Benefits of an ADA Coordinator

There are many benefits to having a knowledgeable ADA coordinator, even for smaller public entities that are not required to have one.

For members of the public, having an ADA Coordinator makes it easy to identify someone to help them with questions and concerns about disability discrimination. For example, the ADA Coordinator is often the main contact when someone wishes to request an auxiliary aid or service for effective communication, such as a sign language interpreter or documents in Braille. A knowledgeable ADA Coordinator will be able to efficiently assist people with disabilities with their questions. She or he will also be responsible for investigating complaints.

Having an ADA Coordinator also benefits state and local government entities. It provides a specific contact person with knowledge and information about the ADA so that questions by staff can be answered efficiently and consistently. In addition, she or he coordinates compliance measures and can be instrumental in ensuring that compliance plans move forward. With the help of this Tool Kit, ADA Coordinators can take the lead in auditing their state or local government’s programs, policies, activities, services, and facilities for ADA compliance.

An Effective ADA Coordinator

The regulations require state and local governments with 50 or more employees to designate an employee responsible for coordinating compliance with ADA requirements. Here are some of the qualifications that help an ADA Coordinator to be effective:

-

familiarity with the state or local government’s structure, activities, and employees

-

knowledge of the ADA and other laws addressing the rights of people with disabilities, such as Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C. § 794

-

experience with people with a broad range of disabilities

-

knowledge of various alternative formats and alternative technologies that enable people with disabilities to communicate, participate, and perform tasks

-

ability to work cooperatively with the local government and people with disabilities

-

familiarity with any local disability advocacy groups or other disability groups

-

skills and training in negotiation and mediation

-

organizational and analytical skills

B. Notice of the ADA’s Provisions

The second administrative requirement is providing public notice about the ADA.2 There are three main considerations for providing notice:

1. Who is the target audience for the ADA notice?

2. What information shall the notice include?

3. Where and how should the notice be provided?

Regardless of Size, the ADA Notice Requirement Applies

The ADA notice requirement applies to ALL state and local governments covered by title II, even localities with fewer than 50 employees.

2 28 C.F.R § 35.106.

1. Who is the target audience for the ADA notice?

The target audience for public notice includes applicants, beneficiaries, and other people interested in the state or local government’s programs, activities, or services. The audience is expansive, and includes everyone who interacts – or would potentially interact – with the state or local government.

Examples of the Target Audience

for the ADA Notice

-

a recipient of social services, food stamps, or financial assistance provided by the state or local government

-

an applicant for a public library card

-

a public transit user

-

a person who uses the county recreation center

-

a grandmother attending her grandchild’s high school graduation in a city park

-

a member of a citizen’s advisory committee

-

a recipient of a grant from the state or local government

-

a citizen who wants to participate in a town council meeting

-

a person adopting a dog from the local public animal shelter

2. What information shall the notice include?

The notice is required to include relevant information regarding Title II of the ADA, and how it applies to the programs, services, and activities of the public entity.

The notice should not be overwhelming. An effective notice states the basics of what the ADA requires of the state or local government without being too lengthy, legalistic, or complicated. It should include the name and contact information of the ADA Coordinator.

This chapter contains a model “Notice Under the Americans with Disabilities Act” created by the Department of Justice. It is a one page document in a standard font, and includes brief statements about:

-

employment,

-

effective communication,

-

making reasonable modifications to policies and programs,

-

not placing surcharges on modifications or auxiliary aids and services, and

-

filing complaints.

The model notice is included at the end of this chapter.

3. How and where should the notice be provided?

It is the obligation of the head of the public entity to determine the most effective way of providing notice to the public about their rights and the public entity’s responsibilities under the ADA.

Publishing and publicizing the ADA notice is not a one-time requirement. State and local governments should provide the information on an ongoing basis, whenever necessary. If you use the radio, newspaper, television, or mailings, re-publish and re-broadcast the notice periodically.

Some Ways to Provide Notice to Interested Persons

-

Include the notice with job applications

-

Publish the notice periodically in local newspapers

-

Broadcast the notice in public service announcements on local radio and television stations

-

Publish the notice on the government entity’s website (ensure that the website is accessible)

-

Post the notice at all facilities

-

Include the notice in program handbooks

-

Include the notice in activity schedules

-

Announce the notice at meetings of programs, services, and activities

-

Publish the notice as a legal notice in local newspapers

-

Post the notice in bus shelters or other public transit stops

The information must be presented so that it is accessible to all. Therefore, it must be available in alternative formats.

Examples of Alternative Formats

-

Audio tape or other recordings

-

Radio announcements

-

Large print notice

-

Braille notice

-

Use of a qualified sign language interpreter at meetings

-

Open or closed-captioned public service announcements on television

-

ASCII, HTML, or word processing format on a computer diskette or CD

-

HTML format on an accessible website

-

Advertisements in publications with large print versions

C. Establishing and Publishing Grievance Procedures

Local governments with 50 or more employees are required to adopt and publish procedures for resolving grievances arising under Title II of the ADA.3 Grievance procedures set out a system for resolving complaints of disability discrimination in a prompt and fair manner.

Neither Title II nor its implementing regulations describe what ADA grievance procedures must include. However, the Department of Justice has developed a model grievance procedure that is included at the end of this chapter.

The grievance procedure should include:

-

a description of how and where a complaint under Title II may be filed with the government entity;

-

if a written complaint is required, a statement notifying potential complainants that alternative means of filing will be available to people with disabilities who require such an alternative;

-

a description of the time frames and processes to be followed by the complainant and the government entity;

-

information on how to appeal an adverse decision; and

-

a statement of how long complaint files will be retained.

Once a state or local government establishes a grievance procedure under the ADA, it should be distributed to all agency heads. Post copies in public spaces of public building and on the government’s website. Update the procedure and the contact information as necessary.

In addition, the procedure must be available in alternative formats so that it is accessible to all people with disabilities.

3 28 C.F.R. § 35.107(b).

Common Question: Complaint Filing

If a person with a disability has a complaint about a public entity, is she or he required to file a complaint with the public entity before filing a complaint with the federal government?

No, the law does not require people who want to file an ADA complaint against a public entity with the federal government to file a complaint with the public entity first. However, it is often more efficient to resolve local problems at a local level.

D. Summing up: ADA Coordinator, Notice, and Grievance Procedures

If a state or local government has fewer than 50 employees, it is required to:

-

adopt and distribute a public notice about the relevant provisions of the ADA to all people who may be interested in its programs, activities, and services.

If a state or local government has 50 employees or more, it is required to:

-

adopt and distribute a public notice about the relevant provisions of the ADA to all persons who may be interested in its programs, activities, and services;

-

designate at least one employee responsible for coordinating compliance with the ADA and investigating ADA complaints; and

-

develop and publish grievance procedures to provide fair and prompt resolution of complaints under Title II of the ADA at the local level.

These administrative requirements help ensure that the needs of people with disabilities are addressed in the programs, activities, and services operated by a public entity. Having these requirements in place will not prevent all problems, but it will help you to address many questions and problems efficiently.

NOTICE UNDER THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT

NOTICE UNDER THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT

In accordance with the requirements of title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 ("ADA"), the [name of public entity] will not discriminate against qualified individuals with disabilities on the basis of disability in its services, programs, or activities.

Employment: [name of public entity] does not discriminate on the basis of disability in its hiring or employment practices and complies with all regulations promulgated by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission under title I of the ADA.

Effective Communication: [Name of public entity] will generally, upon request, provide appropriate aids and services leading to effective communication for qualified persons with disabilities so they can participate equally in [name of public entity’s] programs, services, and activities, including qualified sign language interpreters, documents in Braille, and other ways of making information and communications accessible to people who have speech, hearing, or vision impairments.

Modifications to Policies and Procedures: [Name of public entity] will make all reasonable modifications to policies and programs to ensure that people with disabilities have an equal opportunity to enjoy all of its programs, services, and activities. For example, individuals with service animals are welcomed in [name of public entity] offices, even where pets are generally prohibited.

Anyone who requires an auxiliary aid or service for effective communication, or a modification of policies or procedures to participate in a program, service, or activity of [name of public entity], should contact the office of [name and contact information for ADA Coordinator] as soon as possible but no later than 48 hours before the scheduled event.

The ADA does not require the [name of public entity] to take any action that would fundamentally alter the nature of its programs or services, or impose an undue financial or administrative burden.

Complaints that a program, service, or activity of [name of public entity] is not accessible to persons with disabilities should be directed to [name and contact information for ADA Coordinator].

[Name of public entity] will not place a surcharge on a particular individual with a disability or any group of individuals with disabilities to cover the cost of providing auxiliary aids/services or reasonable modifications of policy, such as retrieving items from locations that are open to the public but are not accessible to persons who use wheelchairs.

[Name of public entity] Grievance Procedure under The Americans with Disabilities Act

This Grievance Procedure is established to meet the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 ("ADA"). It may be used by anyone who wishes to file a complaint alleging discrimination on the basis of disability in the provision of services, activities, programs, or benefits by the [name of public entity]. The [e.g. State, City, County, Town]'s Personnel Policy governs employment-related complaints of disability discrimination.

The complaint should be in writing and contain information about the alleged discrimination such as name, address, phone number of complainant and location, date, and description of the problem. Alternative means of filing complaints, such as personal interviews or a tape recording of the complaint, will be made available for persons with disabilities upon request.

The complaint should be submitted by the grievant and/or his/her designee as soon as possible but no later than 60 calendar days after the alleged violation to:

[Insert ADA Coordinator’s name]

ADA Coordinator [and other title if appropriate]

[Insert ADA Coordinator’s mailing address]

Within 15 calendar days after receipt of the complaint, [ADA Coordinator's name] or [his/her] designee will meet with the complainant to discuss the complaint and the possible resolutions. Within 15 calendar days of the meeting, [ADA Coordinator's name] or [his/her] designee will respond in writing, and where appropriate, in a format accessible to the complainant, such as large print, Braille, or audio tape. The response will explain the position of the [name of public entity] and offer options for substantive resolution of the complaint.

If the response by [ADA Coordinator's name] or [his/her] designee does not satisfactorily resolve the issue, the complainant and/or his/her designee may appeal the decision within 15 calendar days after receipt of the response to the [City Manager/County Commissioner/ other appropriate high-level official] or [his/her] designee.

Within 15 calendar days after receipt of the appeal, the [City Manager/County Commissioner/ other appropriate high-level official] or [his/her] designee will meet with the complainant to discuss the complaint and possible resolutions. Within 15 calendar days after the meeting, the [City Manager/County Commissioner/ other appropriate high-level official] or [his/her] designee will respond in writing, and, where appropriate, in a format accessible to the complainant, with a final resolution of the complaint.

All written complaints received by [name of ADA Coordinator] or [his/her] designee, appeals to the [City Manager/County Commissioner/ other appropriate high-level official] or [his/her] designee, and responses from these two offices will be retained by the [public entity] for at least three years.

Chapter 2 Addendum: Title II Checklist (ADA Coordinator, Notice & Grievance Procedure)

PURPOSE OF THIS CHECKLIST: This checklist is designed for use as an assessment of (1) the requirements and tasks of an ADA Coordinator, (2) the government entity’s provision of the ADA notice, and (3) the government entity’s ADA grievance procedures.

MATERIALS AND INFORMATION NEEDED: To assess compliance with these administrative requirements, you will need:

-

a copy of the written position description for an ADA Coordinator, if applicable;

-

information about the procedures followed by the ADA Coordinator to ensure compliance with the ADA, how complaints are processed, and other tasks performed by the ADA Coordinator;

-

a copy of the written notice or notices used by the state or local government; and

-

a copy of the written grievance procedures used by the state or local government.

ADA Coordinator

1. Does the state or local government have an ADA Coordinator? All state and local governments with 50 or more employees are required to designate at least one responsible employee to coordinate ADA compliance.

◼ Yes, the state or local government has an ADA Coordinator.

◼ No, the state or local government does not have an ADA Coordinator but an ADA Coordinator is not required because the public entity has fewer than 50 employees, including all part-time and full-time employees.

◼ No, the state or local government does not have an ADA Coordinator even though it has 50 or more employees.

ACTIONS:

If the local government has fewer than 50 employees, it is not required to have an ADA coordinator. HOWEVER, it is strongly recommended that an ADA coordinator be appointed.

If the state or local government has 50 or more employees, it must have a designated ADA Coordinator. Any state or local government that does not have an ADA coordinator is in violation of federal law. An ADA Coordinator must be designated.

2. Does the ADA Coordinator have the time and expertise necessary to coordinate the government’s efforts to comply with and carry out its responsibilities under the ADA?

◼ Yes

◼ No

3. Does the ADA coordinator actually carry out these duties?

◼ Yes

◼ No

4. Does the ADA Coordinator investigate all complaints communicated to the government alleging that the government does not comply with the ADA?

◼ Yes

◼ No

5. Does the government make available to all interested people the name, office address, and telephone number of the ADA Coordinator?

◼ Yes

◼ No

ACTIONS:

If you checked “no” for any of the questions above, here are some steps you can take to improve the coordination of your ADA compliance:

-

Ensure that the ADA Coordinator has the time and expertise necessary to coordinate the government’s efforts to comply with and carry out its responsibilities under the ADA.

-

Ensure that the ADA Coordinator actually carries out these duties.

-

Ensure that the ADA Coordinator investigates all complaints communicated to the government alleging that the government does not comply with the ADA.

-

Make available to all interested people the name, office address, and telephone number of the ADA coordinator.

Notice

1. Does the state or local government make information available to the general public regarding the fact that the ADA applies to the services, programs, and activities of the government?

◼ Yes

◼ No

2. Does the state or local government use the Department of Justice’s model “Notice Under the Americans with Disabilities Act” or a similarly comprehensive notice?

◼ Yes

◼ No

3. Does the state or local government post this information in public areas or make it available in other ways as deemed necessary by the head of the government entity to inform people of the protections of the ADA?

◼ Yes

◼ No

4. Is the ADA notice available in alternate formats – i.e., large print, Braille, audio format, accessible electronic format (e.g., via email, in HTML format on its website)?

◼ Yes

◼ No

ACTIONS:

If you checked “no” for any of the questions above, your office may be violating the requirement for providing notice.

-

Make information available to all interested members of the general public regarding the prohibition of discrimination against people with disabilities.

-

Consider using the Department of Justice’s model “Notice Under the Americans with Disabilities Act,” or use a similarly comprehensive notice.

-

Make this information available by posting it in common areas of public buildings, posting it on the government’s website, or otherwise disseminating it as necessary to inform the public of the ADA’s protections.

-

Make the ADA notice available in alternate formats.

Grievance Procedures

1. Does the state or local government have a grievance procedure? All state and local governments with 50 or more employees are required to adopt and publish grievance procedures providing for prompt and fair resolution of complaints of discrimination on the basis of disability.

◼ Yes, the state or local government has a grievance procedure.

◼ No, the state or local government has fewer than 50 employees, including all part-time and full-time employees, and is not required to have a grievance procedure.

◼ No, the state or local government does not have a grievance procedure even though it has 50 or more employees.

2. Does the local government use the Department of Justice’s model “Grievance Procedure under the Americans with Disabilities Act” or a similarly comprehensive grievance procedure (i.e., a grievance procedure for complaints made by any member of the public under the ADA related to any program, service, or activity)?

◼ Yes

◼ No

◼ No, Not applicable, no grievance procedure is required because the public entity has fewer than 50 employees.

3. Is the grievance procedure available in alternate formats?

◼ Yes

◼ No

ACTIONS:

If the local government has fewer than 50 employees, it is not required to have a grievance procedure. HOWEVER, it is strongly recommended that a grievance procedure be adopted and published by all localities subject to title II of the ADA.

If the state or local government has 50 or more employees, it must have a published grievance procedure. Any state or local government that does not have a grievance procedure is in violation of federal law. A grievance procedure must be adopted and published.

-

Consider using the Department of Justice’s model “Grievance Procedure under the Americans with Disabilities Act,” or use a similarly comprehensive grievance procedure.

-

Provide copies of your procedure in alternate formats upon request.

Chapter 3 General Effective Communication Requirements Under Title II of the ADA

In this chapter, you will learn about the requirements of Title II of the ADA for effective communication. Questions answered include:

-

What is effective communication?

-

What are auxiliary aids and services?

-

When is a state or local government required to provide auxiliary aids and services?

-

Who chooses the auxiliary aid or service that will be provided?

A. Providing Equally Effective Communication

Under Title II of the ADA, all state and local governments are required to take steps to ensure that their communications with people with disabilities are as effective as communications with others.1 This requirement is referred to as “effective communication”2 and it is required except where a state or local government can show that providing effective communication would fundamentally alter the nature of the service or program in question or would result in an undue financial and administrative burden.

What does it mean for communication to be “effective”? Simply put, “effective communication” means that whatever is written or spoken must be as clear and understandable to people with disabilities as it is for people who do not have disabilities. This is important because some people have disabilities that affect how they communicate.

How is communication with individuals with disabilities different from communication with people without disabilities? For most individuals with disabilities, there is no difference. But people who have disabilities that affect hearing, seeing, speaking, reading, writing, or understanding may use different ways to communicate than people who do not.

The effective communication requirement applies to ALL members of the public with disabilities, including job applicants, program participants, and even people who simply contact state or local government agencies seeking information about programs, services, or activities.

1 Department of Justice Nondiscrimination on the Basis of State and Local Government Services Regulations, 28 C.F.R. Part 35, § 35.160 (2005). The Department’s Title II regulation is available at www.ada.gov/reg2.htm.

2 See Department of Justice Americans with Disabilities Act Title II Technical Assistance Manual II-7.1000 (1993). The Technical Assistance Manual is available at www.ada.gov/taman2.html.

1. Providing Equal Access With Auxiliary Aids and Services

There are many ways that you can provide equal access to communications for people with disabilities. These different ways are provided through “auxiliary aids and services.” “Auxiliary aids and services” are devices or services that enable effective communication for people with disabilities.3

Title II of the ADA requires government entities to make appropriate auxiliary aids and services available to ensure effective communication.4 You also must make information about the location of accessible services, activities, and facilities available in a format that is accessible to people who are deaf or hard of hearing and those who are blind or have low vision.5

Generally, the requirement to provide an auxiliary aid or service is triggered when a person with a disability requests it.

3 28 C.F.R. §§ 35.104, 35.160.

4 28 C.F.R. Part 35.160(b)(1).

5 28 C.F.R. § 35.163 (a).

2. Different Types of Auxiliary Aids and Services

Here are some examples of different auxiliary aids and services that may be used to provide effective communication for people with disabilities. But, remember, not all ways work for all people with disabilities or even for people with one type of disability. You must consult with the individual to determine what is effective for him or her.

-

qualified interpreters

-

notetakers

-

screen readers

-

computer-aided real-time transcription (CART)

-

written materials

-

telephone handset amplifiers

-

assistive listening systems

-

hearing aid-compatible telephones

-

computer terminals

-

speech synthesizers

-

communication boards

-

text telephones (TTYs)

-

open or closed captioning

-

closed caption decoders

-

video interpreting services

-

videotext displays

-

description of visually presented materials

-

exchange of written notes

-

TTY or video relay service

-

email

-

text messaging

-

instant messaging

-

qualified readers

-

assistance filling out forms

-

taped texts

-

audio recordings

-

Brailled materials

-

large print materials

-

materials in electronic format (compact disc with materials in plain text or word processor format)

B. Speaking, Listening, Reading, and Writing: When Auxiliary Aids and Services Must be Provided

Remember that communication may occur in different ways. Speaking, listening, reading, and writing are all common ways of communicating. When these communications involve a person with a disability, an auxiliary aid or service may be required for communication to be effective. The type of aid or service necessary depends on the length and complexity of the communication as well as the format.

1. Face-to-Face Communications

For brief or simple face-to-face exchanges, very basic aids are usually appropriate. For example, exchanging written notes may be effective when a deaf person asks for a copy of a form at the library.

For more complex or lengthy exchanges, more advanced aids and services are required. Consider how important the communication is, how many people are involved, the length of the communication anticipated, and the context.

Examples of instances where more advanced aids and services are necessary include meetings, hearings, interviews, medical appointments, training and counseling sessions, and court proceedings. In these types of situations where someone involved has a disability that affects communication, auxiliary aids and services such as qualified interpreters, computer-aided real-time transcription (CART), open and closed captioning, video relay, assistive listening devices, and computer terminals may be required. Written transcripts also may be appropriate in pre-scripted situations such as speeches.

Computer-Aided Real-Time Transcription (CART)

Many people who are deaf or hard of hearing are not trained in either sign language or lipreading. CART is a service in which an operator types what is said into a computer that displays the typed words on a screen.

2. Written Communications

Accessing written communications may be difficult for people who are blind or have low vision and individuals with other disabilities. Alternative formats such as Braille, large print text, emails or compact discs (CDs) with the information in accessible formats, or audio recordings are often effective ways of making information accessible to these individuals. In instances where information is provided in written form, ensure effective communication for people who cannot read the text. Consider the context, the importance of the information, and the length and complexity of the materials.

When you plan ahead to print and produce documents, it is easy to print or order some in alternative formats, such as large print, Braille, audio recordings, and documents stored electronically in accessible formats on CDs. Some examples of events when you are likely to produce documents in advance include training sessions, informational sessions, meetings, hearings, and press conferences. In many instances, you will receive a request for an alternative format from a person with a disability before the event.

If written information is involved and there is little time or need to have it produced in an alternative format, reading the information aloud may be effective. For example, if there are brief written instructions on how to get to an office in a public building, it is often effective to read the directions aloud to the person. Alternatively, an agency employee may be able to accompany the person and provide assistance in locating the office.

Don’t forget . . .

Even tax bills and bills for water and other government services are subject to the requirement for effective communication. Whenever a state or local government provides information in written form, it must, when requested, make that information available to individuals who are blind or have low vision in a form that is usable by them.

3. Primary Consideration: Who Chooses the Auxiliary Aid or Service?

When an auxiliary aid or service is requested by someone with a disability, you must provide an opportunity for that person to request the auxiliary aids and services of their choice, and you must give primary consideration to the individual’s choice.6 “Primary consideration” means that the public entity must honor the choice of the individual with a disability, with certain exceptions.7 The individual with a disability is in the best position to determine what type of aid or service will be effective.

The requirement for consultation and primary consideration of the individual’s choice applies to aurally communicated information (i.e., information intended to be heard) as well as information provided in visual formats.

The requesting person’s choice does not have to be followed if:

-

the public entity can demonstrate that another equally effective means of communication is available;

-

use of the means chosen would result in a fundamental alteration in the service, program, or activity; or

-

the means chosen would result in an undue financial and administrative burden.

Video Remote Interpreting (VRI) or Video Interpreting Services (VIS)

VRI or VIS are services where a sign language interpreter appears on a videophone over high-speed Internet lines. Under some circumstances, when used appropriately, video interpreting services can provide immediate, effective access to interpreting services seven days per week, twenty-four hours a day, in a variety of situations including emergencies and unplanned incidents.

On-site interpreter services may still be required in those situations where the use of video interpreting services is otherwise not feasible or does not result in effective communication. For example, using VRI / VIS may be appropriate when doing immediate intake at a hospital while awaiting the arrival of an in-person interpreter, but may not be appropriate in other circumstances, such as when the patient is injured enough to have limited mobility or needs to be moved from room to room.

VRI / VIS is different from Video Relay Services (VRS) which enables persons who use sign language to communicate with voice telephone users through a relay service using video equipment. VRS may only be used when consumers are connecting with one another through a telephone connection.

6 28 C.F.R. Part 35.160(b)(2).

7 See Title II Technical Assistance Manual II-7.1100.

4. Providing Qualified Interpreters and Qualified Readers

When an interpreter is requested by a person who is deaf or hard of hearing, the interpreter provided must be qualified.

A “qualified interpreter” is someone who is able to sign to the individual who is deaf what is being spoken by the hearing person and who can voice to the hearing person what is being signed by the person who is deaf. Certification is not required if the individual has the necessary skills. To be qualified, an interpreter must be able to convey communications effectively, accurately, and impartially, and use any necessary specialized vocabulary.8

Similarly, those serving as readers for people who are blind or have low vision must also be “qualified.”9 For example, a qualified reader at an office where people apply for permits would need to be able to read information on the permit process accurately and in a manner that the person requiring assistance can understand. The qualified reader would also need to be capable of assisting the individual in completing forms by accurately reading instructions and recording information on each form, in accordance with each form’s instructions and the instructions provided by the individual who requires the assistance.

Did You Know That There are Different Types of Interpreters?

Sign Language Interpreters

Sign language is used by many people who are deaf or hard of hearing. It is a visually interactive language that uses a combination of hand motions, body gestures, and facial expressions. There are several different types of sign language, including American Sign Language (ASL) and Signed English.

Oral Interpreters

Not all people who are deaf or hard of hearing are trained in sign language. Some are trained in speech reading (lip reading) and can understand spoken words more clearly with assistance from an oral interpreter. Oral interpreters are specially trained to articulate speech silently and clearly, sometimes rephrasing words or phrases to give higher visibility on the lips. Natural body language and gestures are also used.

Cued Speech Interpreters

A cued speech interpreter functions in the same manner as an oral interpreter except that he or she also uses a hand code, or cue, to represent each speech sound.

5. Television, Videos, Telephones, and Title II of the ADA

The effective communication requirement also covers public television programs, videos produced by a public entity, and telephone communications.10 These communications must be accessible to people with disabilities.

a. Public Television and Videos

If your local government produces public television programs or videos, they must be accessible. A common way of making them accessible to people who are unable to hear the audio portion of these productions is closed captioning. For persons who are blind or have low vision, detailed audio description may be added to describe important visual images.

b. Telephone Communications

Public entities that use telephones must provide equally effective communication to individuals with disabilities. There are two common ways that people who are deaf or hard of hearing and those with speech impairments use telecommunication. One way is through the use of teletypewriters (TTYs) or computer equipment with TTY capability to place telephone calls. A TTY is a device on which you can type and receive text messages. For a TTY to be used, both parties to the conversation must have a TTY or a computer with TTY capability. If TTYs are provided for employees who handle incoming calls, be sure that these employees are trained and receive periodic refreshers on how to communicate using this equipment.