Outdoor Developed Areas: A Summary of Accessibility Standards for Federal Outdoor Developed Areas

Trails

Definition [F106.5]

A trail is defined as a pedestrian route developed primarily for outdoor recreational purposes. Pedestrian routes that are developed primarily to connect accessible elements, spaces, and buildings within a site are not a trail.

The Access Board is developing accessibility guidelines for sidewalks and shared-use paths. The key differences between accessible routes, sidewalks, shared-use paths, and trails are outlined in the appendix of this guide.

New Trails [F247.1]

When a trail is designed for use by hikers or pedestrians and directly connects to a trailhead or another trail that substantially meets the technical requirements for trails, the trail must comply with the technical requirements.

Do the Standards Apply?

-

Is the trail designed for hiker or pedestrian use?

-

Is the trail connected to a trailhead or an existing trail that substantially meets the technical requirements for trails?

The ABA Standards for trails apply when the answer to both questions above is “yes.”

The Federal Trail Data Standards (FTDS) classify trails by their designed use and managed use. Under the FTDS, a trail has only one designed use that determines the design, construction, and maintenance parameters for the trail. A trail can have more than one managed use based on a management decision to allow other uses on the trail. Trails that have a designed use for hikers or pedestrians are required to comply with the technical requirements for trails. Trails that have a designed use for other than hikers or pedestrians, such as mountain bike or equestrian trails, are not required to comply with the technical requirements for trails.

A trail system may include a series of connecting trails. Only trails that directly connect to a trailhead or another trail that substantially meets the technical requirement for trails are required to comply with the technical requirements for trails. A trail that complies with most of the technical requirements for trails is considered to substantially meet the technical requirements.

Existing Trails [F247.2]

When the original design, function, or purpose of an existing trail is changed, regardless of the reason, and the altered portion of the trail directly connects to a trailhead or another trail that substantially meets the technical requirements for trails, the altered portion of the existing trail must comply with the technical requirements for trails.

The term “reconstruction” is not used in the ABA Standards, though the term is used frequently by the trails community. For the purposes of the ABA Standards, actions are categorized as either new construction or an alteration. Routine or periodic maintenance activities are not considered an alteration that would trigger the application of the ABA standards. The difference between an alteration and maintenance is as follows:

-

An alteration is work done to change the original design, purpose, intent, or function of an existing trail.

-

Maintenance is the routine or periodic repair of existing trails or trail segments to restore them to their originally designed and built condition. Maintenance does not change the original design, purpose, intent, or function for which a trail is designed. Maintenance may include:

-

Removing debris and vegetation, such as fallen trees or broken branches on the trail; clearing the trail of encroaching brush or grasses; and removing rock slides

-

Maintaining trail tread, such as filling ruts, reshaping a trail bed, repairing a trail surface or washout, installing riprap to retain cut and fill slopes, and constructing retaining walls or cribbing to support trail tread

-

Performing erosion control and drainage work, such as replacing or installing drainage dips or culverts

-

Repairing or replacing deteriorated, damaged, or vandalized trail or trailhead structures or parts of structures, including sections of bridges, boardwalks, information kiosks, fencing and railings; painting; and removing graffiti

-

Technical Requirements [1017]

The technical requirements for trails include specific provisions for the surface, clear tread width, passing spaces, tread obstacles, openings, running slope, cross slope, resting intervals, protruding objects, and trailhead signs.

Using the Trail Exceptions [1017.1, Exceptions 1 and 2]

When a condition for exceptions does not permit full compliance with a specific provision in the technical requirements on a portion of a trail, that portion of the trail must comply with the specific provision to the extent practicable.

When extreme or numerous conditions for exceptions make it impracticable to construct a trail that complies with the technical requirements, the entire trail can be exempted from complying with the technical requirements. An entire trail can be exempted from the technical requirements only after applying the conditions for exceptions to portions of the trail. When determining whether to exempt an entire trail from the technical requirements, consider the portions of the trail or beach access route that can and cannot comply with the specific provisions in the technical requirements and the extent of compliance where full compliance cannot be achieved.

Additional information on the conditions for exceptions, including documenting use of the exceptions on portions of a trail and notifying the Access Board when an entire trail is exempted from the technical requirements, is provided in the section of this guide on the conditions for exceptions.

Surface [1017.2]

The surfaces of trails, passing spaces, and resting intervals must be firm and stable. A firm trail surface resists deformation by indentations. A stable trail surface is not permanently affected by expected weather conditions and can sustain normal wear and tear from the expected uses between planned maintenances.

Paving with concrete or asphalt may be appropriate for highly developed areas. For less developed areas, crushed stone, fine crusher rejects, packed soil, soil stabilizers, and other natural materials may provide a firm and stable surface. Natural materials also can be combined with synthetic bonding materials to provide greater stability and firmness. These materials may not be suitable for every trail.

DESIGN TIP—Building a firm and stable surface

A firm and stable surface does not always mean concrete and asphalt. Some natural soils can be compacted so that they are firm and stable. Other soils can be treated with stabilizers without drastically changing their appearance. Designers are encouraged to investigate the options and use surfacing materials that are consistent with the site’s level of development and that require as little maintenance as possible.

CONSTRUCTION TIP—Stable materials

Generally, the following materials provide firmer surfaces that are more stable than the alternative:

-

Crushed rock (rather than uncrushed gravel)

-

Rocks with broken faces (rather than rounded rocks)

-

A rock mixture containing a full spectrum of sieve sizes, including fine material (rather than a single size)

-

Hard rock (rather than soft rock that breaks down easily)

-

Rock that passes through a ½-inch screen (rather than larger rocks)

-

Rock material that is compacted in 3- to 4-inch layers (rather than thicker layers)

-

Material that is moist (but not too wet) before it is compacted (rather than material that is compacted when it is dry)

-

Material that is compacted with a vibrating plate compactor, roller, or by hand tamping (rather than material that is laid loose and compacted by use)

Measuring Surface Firmness and Stability

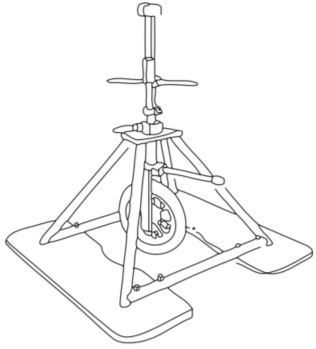

Figure 1—The rotational penetrometer is a portable precision surface indenter that is used for measuring the firmness and stability of surfaces.

The rotational penetrometer (RP) is a precision surface-indenter measuring tool for evaluating the firmness and stability of ground and floor surfaces (figure 1). To measure firmness, the precision spring applies force to the penetrator and the caliper measures the vertical displacement of the penetrator into the surface. The penetrator is then rotated and the total displacement into the surface is measured, indicating surface stability. The Access Board has conducted several research projects using the RP to evaluate the firmness and stability of trail and play area surfaces. Additional information about these projects is available at www.access-board.gov/research /completed-research/accessible-exterior-surfaces. Slip resistance is not required for the surface of trails because leaves, dirt, ice, snow, and other surface debris and weather conditions are part of the natural environment that would be difficult, if not impossible, to avoid.

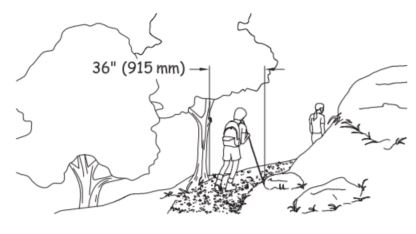

Clear Tread Width [1017.3]

The clear tread width of trails must be a minimum of 36 inches (figure 2). The 36-inch-minimum clear tread width must be maintained for the entire distance of the trail and may not be reduced by gates, barriers, or other obstacles unless a condition for exception does not permit full compliance with the provision.

Figure 2—Minimum clear trail tread width.

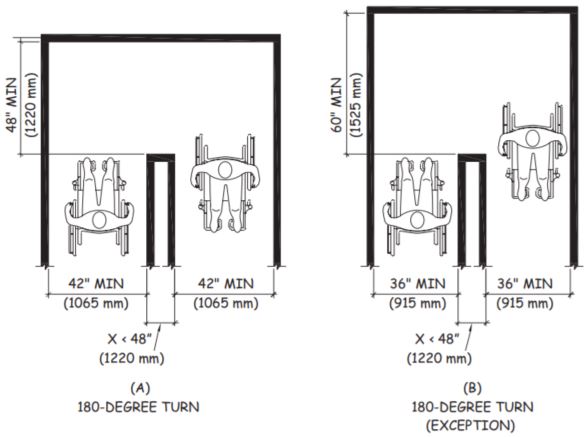

Where gates and barriers require users to make 90-degree or 180-degree turns, sufficient space should be provided for people using mobility devices to make the turns (figure 3). Mobility devices that are used in the outdoors typically have a longer wheel base and are wider than mobility devices that are used indoors. The Access Board and National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research sponsored research to collect anthropometric data from a sample of about 500 people who use manual wheelchairs, power wheelchairs, and scooters. The Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access in the School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York conducted the “Anthropometry of Wheeled Mobility Project.” The final report for this project is available at www.udeworld .com/documents/anthropometry/pdfs/AnthropometryofWheeledMobility Project_FinalReport.pdf. The report recommends that, in order to accommodate 95 percent of the users of manual wheelchairs, power wheelchairs, and scooters in the project sample, a minimum clear width of 43 inches is needed to make a 180-degree turn around a barrier similar to a chicane-style gate.

Figure 3 - 403.5.2 Clear Width at Turn

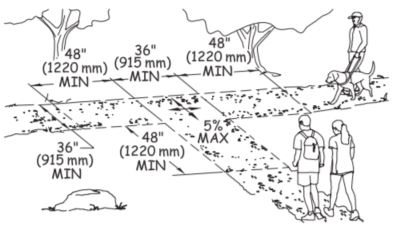

Passing Spaces [1017.4]

A trail tread width less than 60 inches does not permit two people using mobility devices to pass each other. Consequently, where the tread width is less than 60 inches, passing spaces must be provided at intervals of at least 1000 feet. Where the trail is heavily used or the trail is not at the same level as the adjoining ground surface, such as a bridge crossing a ravine, increasing the frequency of passing spaces or widening the tread width to a minimum of 60 inches provides greater access. People using mobility devices also use passing spaces to turn around.

Where the full length of a trail does not fully comply with the trail technical requirements, a passing space must be located at the end of the trail segment that complies fully with the technical requirements. This enables people who use mobility devices to turn around and proceed back to where they started. Consider ways to alert people using mobility devices when a passing space provides the last opportunity on a trail to turn around, because this may not always be apparent. Printed materials, trail Web sites, trailhead information signs, and signage at the end of the trail segment that fully complies with the technical requirements could be used to indicate the location of the last place on the trail to turn around.

Passing spaces must be:

-

A minimum of 60 by 60 inches (figure 4) or

Figure 4—Minimum dimensions for a passing space.

-

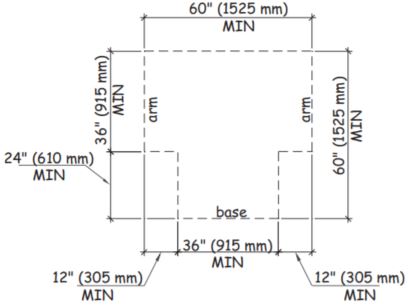

The intersection of two trails that provide a T-shaped space that complies with section 304.3.2 of the ABA Standards (figure 5), and the base and the arms of the T-shaped space extend a minimum of 48 inches beyond the intersection (figure 6)

Figure 5—A T-shaped turning space (304.3.2).

Figure 6—Minimum dimensions for a T-shaped passing space.

Where the intersection of two trails serves as a passing space, the vertical alignment of the trails at the intersection that form the T-shaped space must be nominally planar so that all the wheels of a mobility device remain on the ground when turning into and out of the space. Nominally planar means on the same nominal table surface (same nominal geometric surface plane) and the slopes of the table surface correspond to the running slope and cross slope of the trail tread. For example, if the trail tread has a 2 percent cross slope and 5 percent running slope, the nominal surface plane of the trail tread and passing space must both have a 2 percent cross slope and a 5 percent running slope. This allows people using mobility devices with three or four wheels to better maintain contact with the surface when moving from the main trail into a passing space. This makes it less likely that the mobility device will tip or overbalance to one side.

Passing spaces and resting intervals can overlap. When passing spaces and resting intervals overlap, the technical requirements for resting intervals apply and the slope of the ground surface must be no steeper than 1:48 (2 percent) in any direction. When the surface is constructed of materials other than asphalt, concrete, or boards, slopes no steeper than 1:20 (5 percent) are allowed when necessary for drainage.

Tread Obstacles [1017.5]

A tread obstacle is anything that interrupts the evenness of the tread surface. The vertical alignment of joints in concrete, asphalt, or board surfaces, as well as natural features, such as tree roots and rocks, within the trail tread can be tread obstacles.

The limit on the height of tread obstacles on trails, passing spaces, and resting intervals is based on the surface material used. When the trail surface is constructed of concrete, asphalt, or boards, tread obstacles cannot exceed one-half inch in height at their highest point. When the trail surface is constructed of materials other than concrete, asphalt, or boards, tread obstacles are permitted to be a maximum of 2 inches high.

Frequent tread obstacles and tread obstacles that cross the full width of a trail tread can make travel very difficult for people using mobility devices. Where possible, separate tread obstacles by at least 48 inches, particularly when the obstacles cross the entire tread width. This separation allows people using mobility devices to fully cross one obstacle before confronting another.

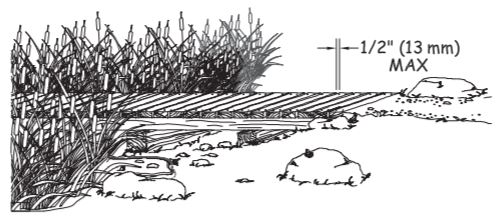

Openings [1017.6]

Openings are gaps in the surface of a trail. Gaps, including slots in a drainage grate and spaces between the planks on a bridge or boardwalk (figure 7), that are big enough for wheels, canes, or crutch tips to drop through or become trapped in are potential hazards.

Openings in the surfaces of trails, passing spaces, and resting intervals must be small enough so that a sphere more than one-half inch in diameter cannot pass through. Where possible, elongated openings should be placed perpendicular, or as close to perpendicular as possible, to the dominant direction of travel.

Figure 7—Where possible, openings in boardwalk decking should be placed perpendicular to the direction of travel.

Running Slope [1017.7.1]

Running slope, also referred to as grade, is the lengthwise slope of a trail, parallel to the direction of travel. Trails or trail segments of any length may be constructed with running slopes up to 1:20 (5 percent). To accommodate steep terrain, trails may be designed with shorter segments that have a running slope and length, as shown in table 2, with resting intervals at the top and bottom of each segment.

| Running Slope of Trail Segment | Maximum Length of Segment | |

| Steeper Than | But Not Steeper Than | |

| 1:20 (5%) | 1:12 (8.33%) | 200 feet |

| 1:12 (8.33%) | 1:10 (10%) | 30 feet |

| 1:10 (10%) | 1:8 (12%) | 10 feet |

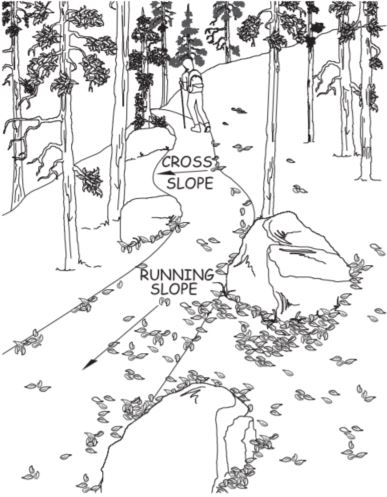

To ensure that a trail is not designed as a series of steep segments, no more than 30 percent of the total length of the trail may have a running slope exceeding 1:12 (8.33 percent). The running slope must never exceed 1:8 (12 percent). Resting intervals must be provided more frequently as the running slope increases (figure 8).

Trail Running Slope

Whenever possible, trails should be constructed with lesser slopes to provide greater independent access and usability.

Figure 8—The running slope is measured along a trail’s length; the cross slope is measured across its width.

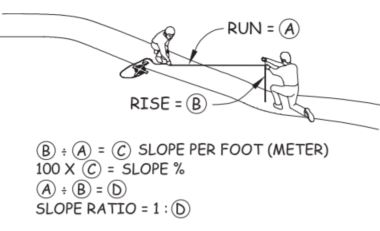

CONSTRUCTION TIP—How is running slope measured?

Running slope is often described as a ratio of vertical distance to horizontal distance, or rise to run (figure 9). For example, a running slope of 1:20 (5 percent) means that for every foot of vertical rise, there are 20 feet of horizontal distance. The technical requirements specify running slope as both a ratio and percentage.

Figure 9—Determining the slope ratio.

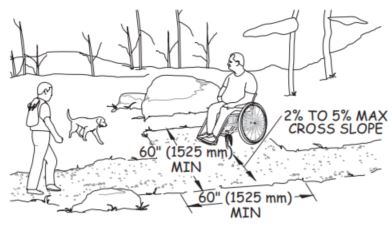

Cross Slope [1017.7.2]

Cross slope is the side-to-side slope of a trail tread. Some cross slope is necessary to provide drainage and to keep water from ponding and damaging the trail surface, especially on unpaved or natural surfaces.

When the trail surface is constructed of concrete, asphalt, or boards, the cross slope must be no steeper than 1:48 (2 percent). When the trail surface is constructed of materials other than asphalt, concrete, or boards, cross slopes no steeper than 1:20 (5 percent) are allowed when necessary for drainage.

Resting Intervals [1017.8]

Resting intervals are level areas that provide an opportunity for people to stop after a steep segment and recover before continuing on. Resting intervals are required between trail segments any time the running slope exceeds 1:20 (5 percent).

Resting intervals may be provided within the trail tread or adjacent to the trail tread. When the resting interval is within the trail tread, it must be at least 60 inches long and at least as wide as the widest segment of the adjacent trail tread.

When the resting interval is adjacent to the trail, it must be at least 60 inches long and 36 inches wide. A turning space that complies with section 304.3.2 of the ABA Standards must be provided. The vertical alignment of the trail tread, turning space, and resting interval must be nominally planar so that all the wheels of a mobility device touch the ground when turning into and out of the resting interval.

When the surface of the resting interval is constructed of concrete, asphalt, or boards, the slope of the resting interval must be no steeper than 1:48 (2 percent) in any direction. When the surface of the resting interval is constructed of materials other than concrete, asphalt, or boards, slopes no steeper than 1:20 (5 percent) are allowed when necessary for drainage.

Protruding Objects [1017.9]

Figure 10—Protruding object requirements do not apply to natural features such as caves in undeveloped areas.

Objects that protrude into the trail clear tread width, passing spaces, and resting intervals can pose hazards to people who are blind or have low vision. Constructed elements on trails, resting intervals, and passing spaces must comply with the technical requirements for protruding objects in section 307 of the ABA Standards. Signs and other post-mounted objects are examples of constructed elements that, if located incorrectly, can be protruding objects.

The technical requirements for protruding objects do not apply to natural features, such as tree branches, rock formations, and trails that pass beneath rock ledges or through caves because these are not constructed elements (figure 10). Clearing limits for trail construction and maintenance usually require that brush, limbs, trees, and logs be cut back a foot or more from the edge of the trail. However, trail maintenance cycles may be several years for some trails, and vegetation may encroach on the trail in the interim between cycles. While it may not always be possible to control vegetation, it is always possible to place constructed features where they won’t pose a hazard to hikers who are blind or have low vision.

User Comments/Questions

Add Comment/Question