Emergency Evacuation Planning Guide For People with Disabilities

CONTAINS PROVISIONS FOR THOSE WITH: Mobility Disabilities • Blind or Low Vision • Deaf or Hard of hearing • Speech Disabilities • Cognitive Disabilities

________________________________________________________________________

© June 2016 National Fire Protection Association

All or portions of this work may be reproduced, displayed or distributed for personal or non-commercial purposes. Commercial reproduction, display or distribution may only be with permission of the National Fire Protection Association.

Emergency Evacuation Planning Guide for People with Disabilities Sign up free NFPA "e-ACCESS" newsletter @ www.nfpa.org/disabilities

Copyright © 2016 National Fire Protection Association All or portions of this work may be reproduced, displayed or distributed for personal or non-commercial purposes. Commercial reproduction, display or distribution may only be with permission of the National Fire Protection Association.

SUMMARY

The NFPA Emergency Evacuation Planning Guide for People with Disabilities has been developed with input from NFPA’s Disability Access Review and Advisory Committee and others in the disability community to provide general information on this important topic. In addition to providing information on the five general categories of disabilities (mobility impairments, visual impairments, hearing impairments, speech impairments, and cognitive impairments), the Guide outlines the four elements of evacuation information that occupants need: notification, way finding, use of the way, and assistance. Also included is a Personal Emergency Evacuation Planning Checklist that building services managers and people with disabilities can use to design a personalized evacuation plan. The annexes give government resources and text based on the relevant code requirements and ADA criteria.

OVERVIEW

The NFPA Emergency Evacuation Planning Guide for People with Disabilities was developed in response to the emphasis that has been placed on the need to properly address the emergency procedure needs of the disability community. This Guide addresses the needs, criteria, and minimum information necessary to integrate the proper planning components for the disabled community into a comprehensive evacuation planning strategy. This Guide is available to everyone in a free, downloadable format from the NFPA website, http://www.nfpa.org/disabilities.

Additionally, a link is available for users of the Guide to provide comments or changes that should be considered for future editions. It is anticipated that the content will be updated annually or more frequently, as necessary, to recognize new ideas, concepts, and technologies.

While building codes in the United States have continuously improved, containing requirements that reduce damage and injury to people and property by addressing fire sprinklers, fire-resistive construction materials, and structural stability, equally important issues such as energy efficiency, protection of heritage buildings, and accessibility are relatively recent subjects that we’ve begun to address in codes.

NFPA's International Operations Department works to develop and increase global awareness of NFPA, its mission, and expertise by promoting worldwide use of NFPA's technical and educational information. Our international offices, covering the Asia/Pacific region, Europe, and Latin America, work to advance the use and adoption of NFPA codes and standards throughout their territories. International staff work closely with government and industry officials, develop and host educational programs, and represent NFPA at seminars and conferences with the aim to improve fire, building, and life safety around the world.

NFPA offers its international members access to the latest fire, building, electrical, and life safety codes and standards. A number of NFPA codes are translated into different languages. NFPA maintains a large presence in Latin America, having established NFPA Chapters in Argentina, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela and offers training seminars in Spanish throughout the region. Additionally, NFPA’s International Operations publishes the NFPA Journal Latinoamericano®, a bilingual fire and life safety magazine in Spanish and Portuguese.

Many newer buildings are constructed as “accessible” or “barrier free” to allow people with disabilities ready access. Equally important is how building occupants with a variety of disabilities are notified of a building emergency, how they respond to a potentially catastrophic event, whether or not appropriate features or systems are provided to assist them during an emergency, and what planning and operational strategies are in place to help ensure “equal egress” during an emergency.

Visual as well as audible fire alarm system components, audible/directional-sounding alarm devices, areas of refuge, stair-descent devices, and other code-based technologies clearly move us in the right direction to address those issues. This Guide is a tool to provide assistance to people with disabilities, employers, building owners and managers, and others as they develop emergency evacuation plans that integrate the needs of people with disabilities and that can be used in all buildings, old and new. The Guide includes critical information on the operational, planning, and response elements necessary to develop a well-thought-out plan for evacuating a building or taking other appropriate action in the event of an emergency. All people regardless of circumstances have some obligation to be prepared to take action during an emergency and to assume responsibility for their own safety.

About NFPA: Founded in 1896, NFPA is a global, nonprofit organization devoted to eliminating death, injury, and property and economic loss due to fire, electrical, and related hazards. The association delivers information and knowledge through more than 300 consensus codes and standards, research, training, education, outreach, and advocacy, and by partnering with others who share an interest in furthering the NFPA mission.

Contact: This Guide was prepared by NFPA staff. Contact Allan B. Fraser, Senior Building Code Specialist, with comments and suggestions at afraser@nfpa.org or 617-984-7411.

PREFACE

The first version of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) that went before Congress was crafted by President Ronald Reagan’s appointees to the National Council on Disability. Even at that time (late 1980s), the disability movement included conservatives as well as liberals and was unified in the view that what was needed was not a new and better brand of social welfare system but a fundamental examination and redefinition of the democratic tradition of equal opportunity and equal rights.

In just two years, Congress passed the ambitious legislation, and in 1990 President George Bush held the largest signing ceremony in history on the south lawn of the White House, a historic moment for all people with disabilities. To some degree, passage of the ADA was brought about by members of Congress realizing their obligation to ensure civil rights for all Americans. The benefits of the ADA extend to a broad range of people by cutting across all sectors of society; virtually everyone has already experienced positive benefits from the law or knows someone who has. According to some studies, as many as two-thirds of people with disabilities are unemployed. This is largely due to attitudinal and physical barriers that prevent their access to available jobs. With a labor-deficit economy, the national sentiment opposed to long-term welfare reliance, and the desire of people with disabilities to be economically independent and self-supporting, employment of people with disabilities is essential.

The ADA is historic not only nationally but globally as well. No other mandate in the world has its scope. Other nations may provide greater levels of support services and assistive technology, but the United States ensures equal rights within a constitutional tradition. The ADA has unique appeal for all Americans because, unlike other civil rights categories such as race and gender, any one of us could become a member of the protected class at any moment in our lives.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) is a codes and standards development organization, not an enforcement agency. The purpose of this Guide is simply to help people with disabilities, employers, building owners and managers, and others look at some of the issues that are relevant to a person’s ability to evacuate a building in the event of an emergency. This document is not intended to be a method or tool for compliance, nor is it a substitute for compliance with any federal, state, or local laws, rules, or regulations. All proposed alternative methods or physical changes should be checked against appropriate codes and enforcing authorities should be consulted to ensure that all proper steps are taken and required approvals are obtained.

It is important to note that employers and building/facility owners and operators have certain legal responsibilities to prevent discrimination against people with disabilities in areas within their control, including but not limited to employment, transportation, housing, training, and access to goods, programs, and activities. Equal facilitation is required for any service provided. Employers and building/facility owners and operators are strongly encouraged to seek guidance from qualified professionals with respect to compliance with the applicable laws for individual programs and facilities. See Annex C for areas covered by the ADA and the ADA Amendments Act.

NFPA may not be able to resolve all the accessibility issues that we face in our lives, but it certainly can provide for accessibility in the built environment where it is regulated through codes and standards.

This Guide has been written to help define, coordinate, and document the information building owners and managers, employers, and building occupants need to formulate and maintain evacuation plans for people with disabilities, whether those disabilities are temporary or permanent, moderate or severe.

USING THIS GUIDE TO DESIGN AN EVACUATION PLAN

This Guide is arranged by disability category. Use the Personal Emergency Evacuation Planning Checklist to check off each step and add the appropriate information specific to the person for whom the plan is being built.

Once the plan is complete, it should be practiced to be sure that it can be implemented appropriately and to identify any gaps or problems that require refinement so that it works as expected. Then copies should be filed in appropriate locations for easy access and given to the assistants, supervisors, co-workers, and friends of the person with the disability; building managers and staff; and municipal departments that may be first responders.

The plan should also be reviewed and practiced regularly by everyone involved. People who have a service animal should practice the evacuation drills with their service animals.

The importance of practicing the plan cannot be overemphasized. Practice solidifies everyone’s grasp of the plan, assists others in recognizing the person who may need assistance in an emergency, and brings to light any weaknesses in the plan.

While standard drills are essential, everyone should also be prepared for the unexpected. Building management should conduct unannounced as well as announced drills and vary the drills to pose a variety of challenges along designated evacuation routes, such as closed-off corridors/stairs, blocked doors, or unconscious people.

Practice and planning do make a difference. During the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, a man with a mobility impairment was working on the 69th floor. With no plan or devices in place, it took over six hours to evacuate him. In the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, the same man had prepared himself to leave the building using assistance from others and an evacuation chair he had acquired and had under his desk. It only took 1 hour and 30 minutes to get him out of the building this second time.

In the case of Brooklyn Center for Independence of the Disabled, a nonprofit organization, Center for Independence of the Disabled, New York, a nonprofit organization, Gregory D. Bell, and Tania Morales vs. Michael R. Bloomberg, in his official capacity as Mayor of the City of New York, and The City of New York, II Civ. 6690 (JMF), in the United States District Court, Southern District of New York, the Court concluded that the City violated the ADA, the Rehabilitation Act, and the NYCHRL by failing to provide people with disabilities meaningful access to its emergency preparedness program in several ways. In particular:

(1) The City's evacuation plans do not accommodate the needs of people with disabilities with respect to high-rise evacuation and accessible transportation;

(2) its shelter plans do not require that the shelter system be sufficiently accessible, either architecturally or programmatically, to accommodate people with disabilities in an emergency;

(3) the City has no plan for canvassing or for otherwise ensuring that people with disabilities - who may, because of their disability, be unable to leave their building after a disaster - are able to access the services provided by the City after an emergency;

(4) the City's plans to distribute resources in the aftermath of a disaster do not provide for accessible communications at the facilities where resources are distributed;

(5) the City's outreach and education program fails in several respects to provide people with disabilities the same opportunity as others to develop a personal emergency plan; and

(6) the City lacks sufficient plans to provide people with disabilities information about the existence and location of accessible services in an emergency.

Emergency evacuation plans should be viewed as living documents. With building management staff, everyone should regularly practice, review, revise, and update their plans to reflect changes in technology, personnel, and procedures.

Chapter 1 GENERAL INFORMATION

Most people will, at some time during their lives, have a disability, either temporary or permanent, that will limit their ability to move around inside or outside a building and to easily use the built environment. In fact, more than one in seven non-institutionalized Americans ages 5 and over have some type of disability (13%); problems with walking and lifting are the most common.

The statistics in the following list are from the 2013 American Community Survey (ACS) published by Cornell University:

-

39.2 million non-institutionalized Americans have one or more disabilities.

-

24.9 million Americans are age 65 or over.

-

9.3 million Americans are age 75 and older.

-

70 percent of all Americans will, at some time in their lives, have a temporary or permanent disability that makes stair climbing impossible.

-

8,000 people survive traumatic spinal cord injuries each year, returning to homes that are inaccessible.

-

11.1 million Americans have serious hearing disabilities.

-

7.3 million Americans have visual disabilities.

-

20.6 million Americans have limited mobility.

Disabilities manifest themselves in varying degrees, and the functional implications of the variations are important for emergency evacuation. One person may have multiple disabilities, while another may have a disability whose symptoms fluctuate. Everyone needs to have a plan to be able to evacuate a building, regardless of his or her physical condition.

While planning for every situation that may occur in every type of an emergency is impossible, being as prepared as possible is important. One way to accomplish this is to consider the input of various people and entities, from executive management, human resources, and employees with disabilities to first responders and other businesses, occupants, and others nearby. Involving such people early on will help everyone understand the evacuation plans and the challenges that businesses, building owners and managers, and people with disabilities face. The issues raised in this Guide will help organizations prepare to address the needs of people with disabilities, as well as others, during an emergency.

This Guide was developed using the five general categories of disabilities recognized in the Fair Housing Act Design Manual. It addresses the four elements of "standard" building evacuation information that apply to everyone but that may require modification or augmentation to be of use to people with disabilities. Most accessibility standards and design criteria are based on the needs of people defined by one of the following five general categories:

The Five General Categories of Disabilities

-

Mobility

-

Blind or Low Vision

-

Deaf or Hard of Hearing

-

Speech

-

Cognitive

The Four Elements of Evacuation Information That People Need

-

Notification (What is the emergency?)

-

Way finding (Where is the way out?)

-

Use of the way (Can I get out by myself, or do I need help?)

-

Self

-

Self with device

-

Self with assistance

-

-

Assistance (What kind of assistance might I need?)

-

Who

-

What

-

Where

-

When

-

How

-

Mobility

Wheelchair Users

People with mobility disabilities may use one or more devices, such as canes, crutches, a power-driven or manually operated wheelchair, or a three-wheeled cart or scooter, to maneuver through the environment. People who use such devices have some of the most obvious access/egress problems. Typical problems include maneuvering through narrow spaces, going up or down steep paths, moving over rough or uneven surfaces, using toilet and bathing facilities, reaching and seeing items placed at conventional heights, and negotiating steps or changes in level at the entrance/exit point of a building.

Ambulatory Mobility Disabilities

This subcategory includes people who can walk but with difficulty or who have a disability that affects gait. It also includes people who do not have full use of their arms or hands or who lack coordination. People who use crutches, canes, walkers, braces, artificial limbs, or orthopedic shoes are included in this category. Activities that may be difficult for people with mobility disabilities include walking, climbing steps or slopes, standing for extended periods of time, reaching, and fine finger manipulation.

Generally speaking, if a person cannot physically negotiate, use, or operate some part or element of a standard building egress system, like stairs or the door locks or latches, then that person has a mobility impairment that affects his or her ability to evacuate in an emergency unless alternatives are provided.

Respiratory

People with a respiratory impairments can generally use the components of the egress system but may have difficulty safely evacuating due to dizziness, nausea, breathing difficulties, tightening of the throat, or difficulty concentrating. Such people may require rest breaks while evacuating.

Blind or Low Vision

This category includes people with partial or total vision loss. Some people with a visual disability can distinguish light and dark, sharply contrasting colors, or large print but cannot read small print, negotiate dimly lit spaces, or tolerate high glare. Many people who are blind depend on their sense of touch and hearing to perceive their environment. For assistance while in transit, walking, or riding, many people with visual impairments use a white cane or have a service animal. There is a risk that a person with a visual impairment would miss a visual cue, such as a new obstruction that occurred during the emergency event, that could affect egress.

Generally speaking, if a person cannot use or operate some part or element of a standard building egress system or access displayed information, like signage, because that element or information requires vision in order to be used or understood, then that person has a visual impairment that could affect his or her ability to evacuate in an emergency unless alternatives are provided.

Deaf or Hard of Hearing

People with partial hearing often use a combination of speech reading and hearing aids, which amplify and clarify available sounds. Echo, reverberation, and extraneous background noise can distort hearing aid transmission. People who are deaf or hard of hearing and who rely on lip reading for information must be able to clearly see the face of the person who is speaking. Those who use sign language to communicate may be adversely affected by poor lighting. People who are hard of hearing or deaf may have difficulty understanding oral communication and receiving notification by equipment that is exclusively auditory, such as telephones, fire alarms, and public address systems. There is a risk that a person with a hearing loss or deafness would miss an auditory cue to the location of a dangerous situation, affecting his or her ability to find safe egress.

Generally speaking, if a person cannot receive some or all of the information emitted by a standard building egress system, like a fire alarm horn or voice instructions, then that person has a hearing impairment that could affect his or her ability to evacuate in an emergency unless alternatives are provided.

Speech Disabilities

A speech disability prevents a person from using or accessing information or building features that require the ability to speak. Speech impairments can be caused by a wide range of conditions, but all result in some level of loss of the ability to speak or to verbally communicate clearly.

The only “standard” building egress systems that may require a person to have the ability to speak in order to evacuate a building are the emergency phone systems in areas of refuge, elevators, or similar locations. These systems need to be assessed in the planning process.

Cognitive Disabilities

A cognitive disability prevents a person from using or accessing building features due to an inability to process or understand the information necessary to use those features.

Cognitive disabilities can be caused by a wide range of conditions, including, but not limited to, developmental disabilities, multiple sclerosis, depression, alcoholism, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, traumatic brain injury, chronic fatigue syndrome, stroke, and some psychiatric conditions, but all result in some decreased or impaired level in the ability to process or understand the information received by the senses.

All standard building egress systems require a person to be able to process and understand information in order to safely evacuate a building.

Other Disabilities and Multiple Disabilities

In addition to people with permanent or long-term disabilities, there are others who have temporary conditions that affect their usual abilities. Broken bones, illness, trauma, or surgery can affect a person’s use of the built environment for a short time. Diseases of the heart or lungs, neurological diseases with a resulting lack of coordination, arthritis, and rheumatism can reduce a person’s physical stamina or cause pain. Other disabilities include multiple chemical sensitivities and seizure disorders. Reduction in overall ability is also experienced by many people as they age. People of extreme size or weight often need accommodation as well.

It is not uncommon for people to have multiple disabilities. For example, someone could have a combination of visual, speech, and hearing disabilities. Evacuation planning for people with multiple disabilities is essentially the same process as for those with individual disabilities, although it will require more steps to develop and complete more options or alternatives.

SERVICE ANIMALS

Service animals assist people with disabilities in their day-to-day activities. While most people are familiar with guide dogs trained to assist people with blind or low vision, animals can be trained for a variety of tasks, including alerting a person to sounds in the home and workplace, pulling a wheelchair, picking up items, or assisting with balance.

Service animals are defined as dogs that are individually trained to do work or perform tasks for a person with a disability. Examples of such work or tasks include guiding people who are blind or low vision, alerting people who are deaf, pulling a wheelchair, alerting and protecting a person who is having a seizure, reminding a person with mental illness to take prescribed medications, calming a person with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) during an anxiety attack, or performing other duties. Service animals are working animals, not pets. The work or task a dog has been trained to provide must be directly related to the person’s disability. Dogs whose sole function is to provide comfort or emotional support do not qualify as service animals under the ADA.

In addition to the provisions about service dogs, the Department’s revised ADA regulations have a new, separate provision about miniature horses that have been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities. (Miniature horses generally range in height from 24 inches to 34 inches measured to the shoulders and generally weigh between 70 and 100 pounds.) Entities covered by the ADA must modify their policies to permit miniature horses where reasonable. The regulations set out four assessment factors to assist entities in determining whether miniature horses can be accommodated in their facility. The assessment factors are (1) whether the miniature horse is housebroken; (2) whether the miniature horse is under the owner’s control; (3) whether the facility can accommodate the miniature horse’s type, size, and weight; and (4) whether the miniature horse’s presence will not compromise legitimate safety requirements necessary for safe operation of the facility.

Under the ADA, State and local governments, businesses, and nonprofit organizations that serve the public generally must allow service animals to accompany people with disabilities in all areas of the facility where the public is normally allowed to go. For example, in a hospital it would be inappropriate to exclude a service animal from areas such as patient rooms, clinics, cafeterias, or examination rooms. However, it may be appropriate to exclude a service animal from operating rooms or burn units where the animal’s presence may compromise a sterile environment.

Under the ADA, service animals must be harnessed, leashed, or tethered, unless these devices interfere with the service animal’s work or the individual’s disability prevents using these devices. In that case, the individual must maintain control of the animal through voice, signal, or other effective controls.

Only under the following rare and unusual circumstances can a service animal be excluded from a facility:

-

The animal’s behavior poses a direct threat to the health or safety of others.

-

The animal’s presence would result in a fundamental alteration to the nature of a business or a state or local government’s program or activity.

-

The animal would pose an "undue hardship" for an employer. Such instances would include a service animal that displays vicious behavior toward visitors or co-workers or a service animal that is out of control. Even in those situations, the public facility, state or local government, or employer must give the person with a disability the opportunity to enjoy its goods, services, programs, activities, and/or equal employment opportunities without the service animal (but perhaps with some other accommodation).

A person with a service animal should relay to emergency management personnel his or her specific preferences regarding the evacuation and handling of the animal. Those preferences then need to be put in the person’s evacuation plan and shared with the appropriate building and management personnel.

People with service animals should also discuss how they can best be assisted if the service animal becomes hesitant or disoriented during the emergency situation. The procedure should be practiced so that everyone, including the service animal, is comfortable with it.

First responders should be notified of the presence of a service animal and be provided with specific information in the evacuation plan. Extra food and supplies should be kept on hand for the service animal.

STANDARD BUILDING EVACUATION SYSTEMS

A standard building evacuation system has three components:

1. The circulation path

2. The occupant notification system(s)

3. Directions to and through the circulation paths

Circulation Path

A circulation path is a continuous and unobstructed way of travel from any point in a building or structure to a public way.

The components of a circulation path include but are not limited to rooms, corridors, doors, stairs, smokeproof enclosures, horizontal exits, ramps, exit passageways, escalators, moving walkways, fire escape stairs, fire escape ladders, slide escapes, alternating tread devices, areas of refuge, and elevators.

A circulation path is considered a usable circulation path if it meets one of the following criteria:

-

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through the circulation path to a public way.

-

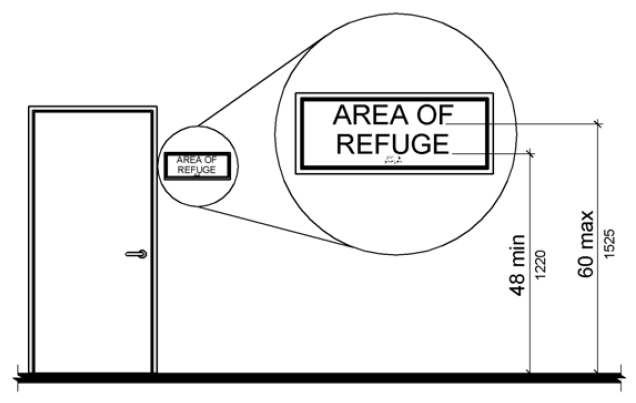

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through that portion of the circulation path necessary to reach an area of refuge. (See 7.2.12 of NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, for more information.)

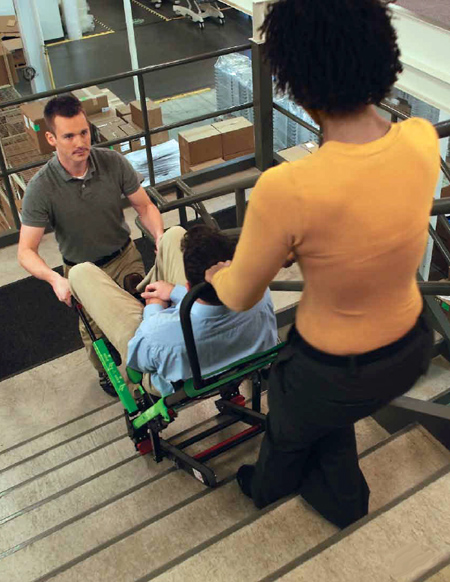

An area of refuge serves as a temporary haven from the effects of a fire or other emergency. The person with disabilities must have the ability to travel from the area of refuge to the public way, although such travel might depend on the assistance of others. If elevation differences are involved, an elevator or other evacuation device might be used, or the person might be moved by other people using a cradle carry, a swing (seat) carry, or an in-chair carry or by a stair descent device. (See 7.2.12 of NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, for more information.)

A usable circulation path would also be one that complies with the applicable requirements of ICC/ANSI A117.1, American National Standard for Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities, for the particular disabilities involved.

Occupant Notification System

The occupant notification systems include but are not limited to alarms and public address systems.

NFPA 72®, National Fire Alarm Code, defines a notification appliance as "a fire alarm system component such as a bell, horn, speaker, light, or text display that provides audible, tactile, or visible outputs, or any combination thereof."

Directions to and through the Usable Circulation Path

Directions to and through the usable circulation path include signage, oral instructions passed from person to person, and instructions, which may be live or automated, broadcast over a public address system.

Personal notification devices, which have recently come onto the market, can be activated in a number of ways, including but not limited to having a building’s alarm system relay information to the device. The information can be displayed in a number of forms and outputs. Because this technology is new to the market, such devices and systems are not discussed here; however, emergency evacuation personnel and people with disabilities may want to investigate them further.

OCCUPANT NOTIFICATION SYSTEMS

No Special Requirements. People with limited mobility can hear standard alarms and voice announcements and can see activated visual notification appliances (strobe lights) that warn of danger and the need to evacuate. No additional planning or special accommodations for this function are required.

Is There a Usable Circulation Path?

A circulation path is considered a usable circulation path if it meets one of the following criteria:

-

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through it to a public way.

-

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through that portion of the circulation path necessary to reach an area of refuge.

An area of refuge serves as a temporary haven from the effects of a fire or other emergency. A person with a severe mobility impairment must have the ability to travel from the area of refuge to the public way, although such travel might depend on the assistance of others. If elevation differences are involved, an elevator or other evacuation device might be used, or others might move the person by using a wheelchair carry on the stairs.

Special Note 1

People with limited mobility need to know if there is a usable circulation path from the building they are in. If there is not a usable circulation path, then their plans will require alternative routes and methods of evacuation to be put in place.

Which Circulation Paths Are Usable Circulation Paths?

Exits, other than main exterior exit doors that obviously and clearly are identifiable as exits, should be marked by approved signs that are readily visible from any direction of approach in the exit access.

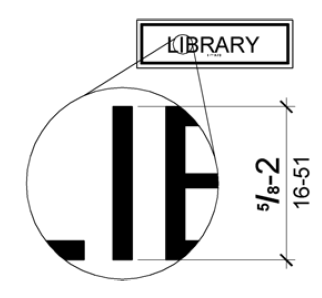

Where not all circulation paths are usable by people with disabilities, the usable circulation path(s) should be clearly identified by the international symbol of accessibility:

Locations of exit signs and directional exit signs are specified by model codes. Usually the signs are placed above exit doors and near the ceiling.

Supplemental directional exit signs may be necessary to clearly delineate the route to the exit. Exit signs and directional exit signs should be located so they are readily visible and should contrast against their surroundings.

Special Note 2

People with limited mobility should be provided with some form of written directions, a brochure, or a map showing all directional signs to all usable circulation paths. For new employees and other regular users of the facility it may be practical to physically show them the usable circulation paths as well as provide them with written information. In addition, simple floor plans of the building that show the locations of and routes to usable circulation paths should be available and given to visitors with limited mobility when they enter the building. A large sign could be posted at each building entrance stating the availability of written directions or other materials and where to pick them up. Building security personnel, including those staffing entrance locations, should be trained in all the building evacuation systems for people with disabilities and be able to direct anyone to the nearest usable circulation path.

Which Paths Lead to Usable Circulation Paths?

Any circulation paths that are not usable should include signs directing people to other, usable paths. People with limited mobility should be provided with written directions, a brochure, or a map showing what those signs look like and where they are.

Special Note 3

Where such directional signs are not in place, people with limited mobility should be provided with written directions, a brochure, or a map showing the locations of all usable circulation paths.

Can People with Limited Mobility Use the Usable Circulation Path by Themselves?

Is There a Direct Exit to Grade (or a Ramp)?

A circulation path is considered a usable circulation path if it meets one of the following criteria:

-

A person using a wheelchair is able to travel unassisted through it to a public way (if elevation differences are involved, there are usable ramps rather than stairs).

-

A person using a wheelchair is able to travel unassisted through that portion of the usable circulation path necessary to reach an area of refuge.

An area of refuge serves as a temporary haven from the effects of a fire or other emergency. People with limited mobility must be able to travel from the area of refuge to the public way, although such travel might depend on the assistance of others. If elevation differences are involved, an elevator or other evacuation device might be used, or the person might be moved by another person or persons using a cradle carry, a swing (seat) carry, or an in-chair carry. Training, practice, and an understanding of the benefits and risks of each technique for a given person are important aspects of the planning process.

Special Note 4

Not all people using wheelchairs or other assistive devices are capable of navigating a usable circulation path by themselves. It is important to verify that each person using any assistive device can travel unassisted through the usable circulation path to a public way. Those who cannot must have the provision of appropriate assistance detailed in their emergency evacuation plans. Additionally, the plans should provide for evacuation of the device or the availability of an appropriate alternative once the person is outside the building. Otherwise, the person with limited mobility will no longer have independent mobility once he or she is out of the emergency situation.

Can the Person with Limited Mobility Use Stairs?

Not all people with limited mobility use wheelchairs. Some mobility limitations prevent a person from using building features that require the use of one’s arms, hands, fingers, legs, or feet. People with limited mobility may be able to go up and down stairs easily but have trouble operating door locks, latches, and other devices due to impairments of their hands or arms. The evacuation plans for these people should address alternative routes, alternative devices, or specific provisions for assistance. Are there devices to help people with limited mobility evacuate?

Can the Elevators Be Used?

Although elevators can be a component of a usable circulation path, restrictions are imposed on the use of elevators during some types of building emergencies. Elevators typically return to the ground floor when a fire alarm is activated and can be operated after that only by use of a “fire fighters” keyed switch. This may not be true in the event of non-fire emergencies requiring an evacuation. In the last several years, however, building experts have increasingly joined forces to carefully consider building elevators that are safer for use in the event of an emergency.

In October 2003, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) began working with the elevator industry to develop and test more reliable emergency power systems and waterproof components. Under consideration are software and sensing systems that adapt to changing smoke and heat conditions, helping to maintain safe and reliable elevator operation during fire emergencies. Such changes could allow remote operation of elevators during fires, thus freeing fire fighters to assist in other ways during an emergency.

The topic was further examined in 2010 during the Workshop on the Use of Elevators in Fires and Other Emergencies cosponsored by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME International), NIST, the International Code Council (ICC), the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), the U.S. Access Board, and the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF). The workshop provided a forum for brainstorming and formulating recommendations in an effort to improve codes and standards.

The majority of recommendations led to the formation of two new ASME task groups: the Use of Elevators by Fire Fighters task group and the Use of Elevators for Occupant Egress task group, and new code requirements. This work was a collaborative effort of ASME, NIST, ICC, NFPA, IAFF, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the U.S. Access Board.

Here again, good planning and practice are key elements of a successful evacuation.

Are Lifts Available?

Lifts generally have a short vertical travel distance, usually less than 10 feet, and therefore can be an important part of an evacuation. Lifts should be checked to make sure they have emergency power, can operate if the power goes out, and if so, for how long or how many uses. It is important to know whether the building’s emergency power comes on automatically or a switch or control needs to be activated.

What Other Devices Are Available?

Some evacuation devices and methods, including stair-descent devices, require the assistance of others.

Who Will Provide the Assistance?

Anyone in the Office or Building

People with limited mobility who are able to go up and down stairs easily but have trouble operating door locks, latches, and other devices due to limitations of their hands or arms can be assisted by anyone. A viable plan to address this situation may be for the person with the disability to be aware that he or she will need to ask someone for assistance with a particular door or a particular device. It is important to remember that not everyone in a building is familiar with all the various circulation paths everywhere in the building and that they may have to use an unfamiliar one in the event of an emergency.

Specific Person(s) in the Office or Building

-

Friend or coworker

-

Relative

-

Supervisor

-

Building staff

-

Floor safety warden

-

-

First responders

-

Floor safety warden

-

Fire fighter

-

Police officer

-

Emergency medical services: emergency medical technicians (EMTs), ambulance personnel

-

How Many People Are Necessary to Provide Assistance?

One Person

When only one person is necessary to assist a person with limited mobility , a practical plan should identify at least two, ideally more, people who are willing and able to provide assistance. Common sense tells us that a specific person may not be available at any given time due to illness, vacation, an off-site meeting, and so on. The identification of multiple people who are likely to have different working and traveling schedules provides a more reliable plan.

Multiple People

When more than one person is necessary to assist a person with limited mobility, a practical plan should identify at least twice the number of people required who are willing and able to provide assistance. Common sense tells us that one or more specific people may not be available at any given time due to illness, vacation, off-site meetings, and so on. The identification of a pool of people who are likely to have different working and traveling schedules provides a more reliable plan.

What Assistance Will the Person(s) Provide?

Guidance

-

Explaining how and where the person needs to go to get to the usable circulation path

-

Escorting the person to and/or through the usable circulation path

Minor Physical Effort

-

Offering an arm to assist the person to/through the usable circulation path

-

Opening the door(s) in the usable circulation path

Major Physical Effort

-

Operating a stair-descent device

-

Participating in carrying a wheelchair down the stairs

-

Carrying a person down the stairs

Waiting for First Responders

Waiting with the person with limited mobility for first responders would likely be a last choice when there is an imminent threat to people in the building. While first responders do their best to get to a site and the particular location of those needing their assistance, there is no way of predicting how long any given area will remain a safe haven under emergency conditions.

This topic should be discussed in the planning stage. Agreement should be reached regarding how long the person giving assistance is expected to wait for the first responders to arrive. Such discussion is important because waiting too long can endanger more lives. If someone is willing to delay his or her own evacuation to assist a person with limited mobility in an emergency, planning how long that wait might be is wise and reasonable.

Where Will the Person(s) Start Providing Assistance?

From the Location of the Person Requiring Assistance

Does the person providing assistance need to go where the person with limited mobility is located at the time the alarm sounds? If so, how will he or she know where the person needing assistance is?

-

Face to face

-

Phone

-

PDA

-

E-mail

-

Visual

-

Other

From a Specific, Predetermined Location

-

Entry to stairs

-

Other

When Will the Person(s) Provide Assistance?

-

Always

-

Only when asked

-

Other

How Will the Person(s) Providing Assistance Be Contacted?

-

Face to face

-

Phone

-

PDA

-

E-mail

-

Visual

-

Other

OCCUPANT NOTIFICATION SYSTEMS

No Special Requirements. People who are blind or have low vision can hear standard building fire alarms and voice announcements over public address systems that warn of a danger or the need to evacuate or that provide instructions. Therefore, no additional planning or special accommodations for this function are required.

Is There a Usable Circulation Path?

A circulation path is considered a usable circulation path if it meets one of the following criteria:

-

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through it to a public way.

-

A person with disabilities is able to travel unassisted through that portion of the circulation path necessary to reach an area of refuge.

An area of refuge is a space that serves as a temporary haven from the effects of a fire or other emergency. A person who is blind or has low vision must be able to travel from the area of refuge to the public way, although such travel might depend on the assistance of others.

Special Note 5

A person who is blind or has low vision needs to know if there is a usable circulation path from the building. If there is not a usable circulation path, then the personal emergency evacuation plan for that person will require that alternative routes and methods of evacuation be put in place.

For People with Disabilities, Which Circulation Paths Are Usable, Available, and Closest?

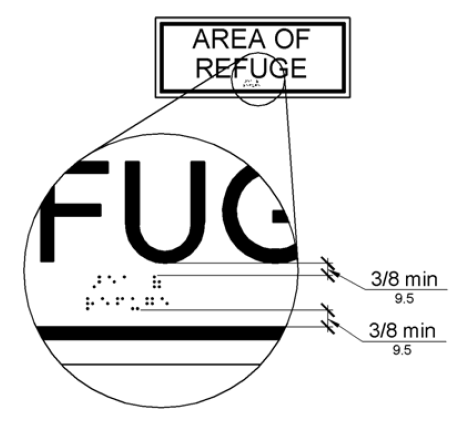

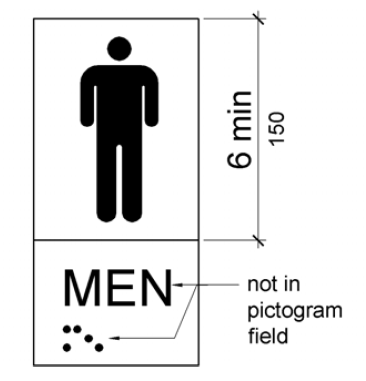

Exits should be marked by tactile signs that are properly located so they can be readily found by a person who is blind or has low vision from any direction of approach to the exit access.

Where not all circulation paths are usable by people with disabilities, the usable circulation paths should be identified by the tactile international symbol of accessibility:

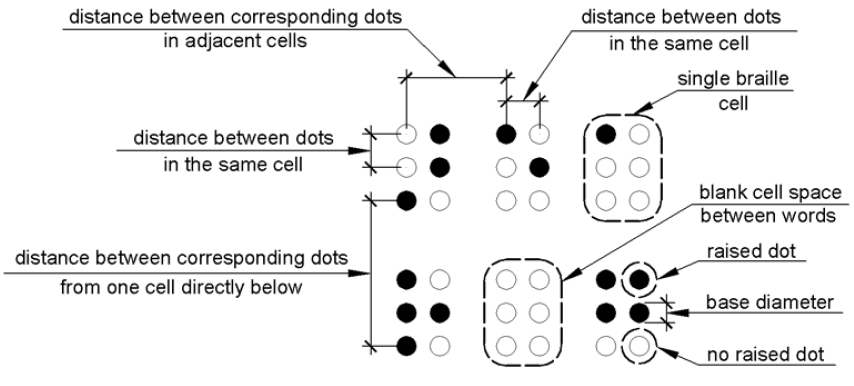

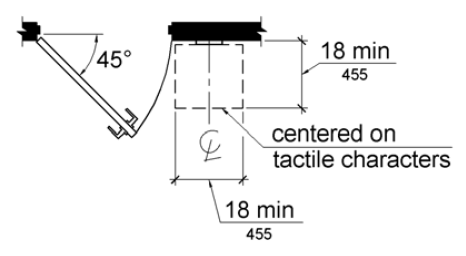

The location of exit signage and directional signage for those with visual impairments is clearly and strictly specified by codes. The requirements include but are not limited to the type, size, spacing, and color of letters for visual characters and the type, size, location, character height, stroke width, and line spacing of tactile letters or braille characters. The specific code requirements are included in Annex C.

Special Note 6

It may be practical to physically take new employees who are blind or have low vision to and through the usable circulation paths and to all locations of directional signage to usable circulation paths. In addition, simple floor plans of the building indicating the location of and routes to usable circulation paths should be available in alternative formats such as single-line, high-contrast plans. These plans should be given to visitors who are blind or have low vision when they enter the building so they can find the exits in an emergency. Tactile and braille signs should be posted at the building entrances stating the availability of the floor plans and where to pick them up. Building security personnel, including those staffing the entrances, should be trained in all accessible building evacuation systems and be able to direct anyone to the nearest usable circulation path.

Special Note 7

The personal evacuation plan for a person who is blind or has low vision needs to be prepared and kept in the alternative format preferred by that person, including but not limited to braille, large type, or tactile characters.

Which Paths Are Usable Circulation Paths?

Tactile directional signs that indicate the location of the nearest usable circulation path should be provided at all circulation paths that are not usable by people with disabilities. It may be practical to physically show new employees who are blind or have low vision where all usable circulation paths are.

Special Note 8

Where tactile directional signs are not in place, it may be practical to physically show new employees who are blind or have low vision where all usable circulation paths are located. Building management should consider installing appropriate visual, tactile, and/or braille signage in appropriate locations conforming to the code requirements in Annex C. Installing such signage is generally not expensive. Building owners and managers may be unaware that there is something they can do to facilitate the safe evacuation of people who are blind or have low vision.

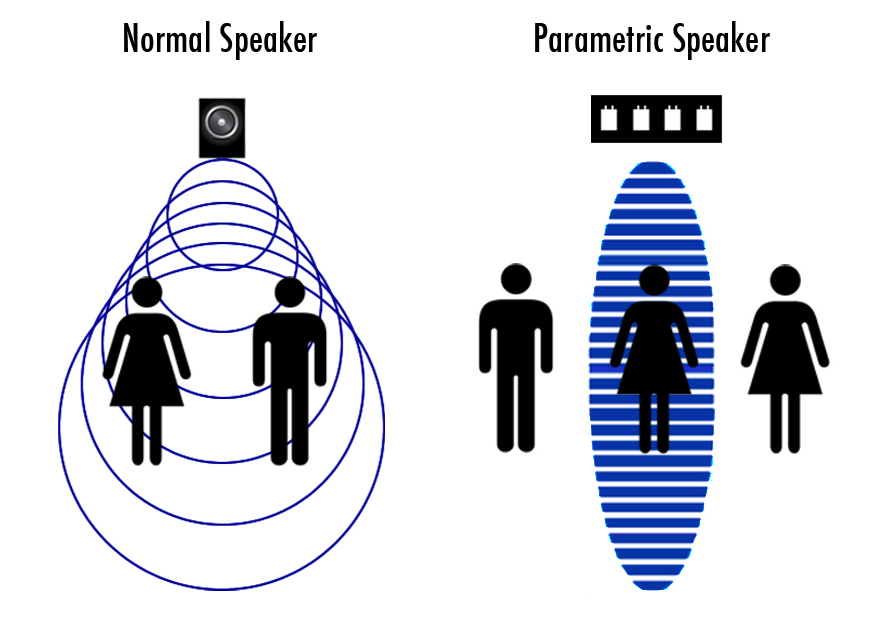

A new technology in fire safety generically called “directional sound” is on the market. Traditional fire alarm systems are designed to notify people but not necessarily to guide them. Directional sound is an audible signal that leads people to safety in a way that conventional alarms cannot, by communicating the location of exits using broadband noise. The varying tones and intensities coming from directional sound devices offer easy-to-discern cues for finding the way out. As soon as people hear the devices, they intuitively follow them to get out quickly. While not yet required by any codes, directional sound is a technology that warrants investigation by building services management.

Can People Who are Blind or Have Low Vision Use the Circulation Path by Themselves?

A circulation path is considered a usable circulation path if it meets one of the following criteria:

-

A person who is blind or has low vision is able to travel unassisted through it to a public way.

-

A person who is blind or has low vision is able to travel unassisted through that portion of the usable circulation path necessary to reach an area of refuge.

An area of refuge serves as a temporary haven from the effects of a fire or other emergency. A person who is blind or has low vision must be able to travel from the area of refuge to the public way, although such travel might depend on the assistance of others. If elevation differences are involved, an elevator might be used, or the person might be led down the stairs.

Will a Person Who is Blind or Has Low Vision Require Assistance to Use the Circulation Path?

Not all people who are blind or have low vision are capable of navigating a usable circulation path. It is important to verify that a person who is blind or has low vision can travel unassisted through the exit access, the exit, and the exit discharge to a public way. If he or she cannot, then that person’s personal emergency evacuation plan will include a method for providing appropriate assistance.

Generally, only one person is necessary to assist a person who is blind or has low vision. A practical plan is to identify at least two, ideally more, people who are willing and able to provide assistance. Common sense tells us that a specific person may not be available at any given time due to illness, vacation, off-site meetings, and so on. The identification of multiple people who are likely to have different working and traveling schedules provides a much more reliable plan.

Who Will Provide the Assistance?

Anyone in the Office or the Building

People with visual impairments who are able to go up and down stairs easily but simply have trouble finding the way or operating door locks, latches, and other devices can be assisted by anyone. A viable plan may simply be for the person with a visual impairment to be aware that he or she will need to ask someone for assistance.

Specific Person(s) in the Office or the Building

-

Friend or co-worker

-

Relative

-

Supervisor

-

Building staff

-

Floor safety warden

-

-

First responders

-

Floor safety warden

-

Fire fighter

-

Police officer

-

Emergency medical services: emergency medical technicians (EMTs), ambulance personnel

-

What Assistance Will the Person(s) Provide?

Guidance

-

Explaining how to get to the usable circulation path

-

Escorting the person who is blind or has low vision to and/or through the circulation path

Minor Physical Effort

-

Offering the person an arm or allowing the person to place a hand on your shoulder and assisting the person to/through the circulation path

-

Opening doors in the circulation path

Waiting for First Responders

Generally speaking, a person who is blind or has low vision will not need to wait for first responders. Doing so would likely be a last choice when there is an imminent threat to people in the building. While first responders do their best to get to a site and the particular location of those needing their assistance, there is no way to predict how long any given area will remain a safe haven under emergency conditions.

Where Will the Person(s) Start Providing Assistance?

From the Location of the Person Requiring Assistance

Does the person providing assistance need to go where the person who is blind or has low vision is located at the time the alarm sounds? If so, how will he or she know where the person needing assistance is?

-

Phone

-

PDA

-

E-mail

-

Visual

-

Other

From a Specific, Predetermined Location

-

Entry to stairs

-

Other

When Will the Person(s) Provide Assistance?

-

Always

-

Only when asked

-

Other

How Will the Person(s) Providing Assistance Be Contacted?

-

Face to face

-

Phone

-

PDA

-

E-mail

-

Visual

-

Other

Visual Devices for the Fire Alarm System

People who are deaf or hard of hearing cannot hear alarms and voice announcements that warn of danger and the need to evacuate. Many codes require new buildings to have flashing strobe lights (visual devices) as part of the standard building alarm system, but because the requirements are not retroactive many buildings don’t have them. In addition, strobes are required only on fire alarm systems and simply warn that there may be a fire. Additional information that is provided over voice systems for a specific type of emergency such as a threatening weather event, or that directs people to use a specific exit, are unavailable to people who are deaf or hard of hearing.

It is extremely important for people who are deaf or hard of hearing to know what, if any, visual notification systems are in place. They also need to be aware of which emergencies will activate the visual notification system and which emergencies will not. Alternative methods of notification need to be put into the emergency evacuation plans for people who are deaf or hard of hearing so they can get all the information they need to evacuate in a timely manner.

Devices or Methods for Notification of Other Emergencies

The following is a partial list of emergencies that should be considered in the development of alternative warning systems:

-

Natural events

-

Storms (hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, snow, lightning, hail, etc.)

-

Earthquakes (Although a system would provide only a few seconds’ notice, it may lessen anxiety and prevent panic.)

-

-

Human-caused events (robbery, hostile acts, random violence, etc.)

Special Note 9

Scrolling reader boards are becoming more common and are being applied in creative ways. In emergency situations, they can flash to attract attention and provide information about the type of emergency or situation. Some major entertainment venues use this technology to provide those who are deaf or hard of hearing with “closed captioning” at every seat, for very little cost. A reversed scrolling reader board is mounted in the back of the room. Guests who are deaf or hard of hearing are provided with small teleprompter-type screens mounted on small stands. The guests place the stands directly in front of themselves and adjust the screens so they can see the reader board reflected off the screens. The screens are transparent, so they don’t block the view of guests behind the screen users.

If a person who is deaf or hard of hearing is likely to be in one location for a significant period of time, such as at a desk in an office, installation of a reader board in the work area might be considered to provide appropriate warning in an emergency.

Personal notification devices are also coming on the market. Such devices can be activated in a number of ways, including having a building’s alarm system relay information to the device. Information can be displayed in a variety of forms and outputs.

E-mail and TTY phone communications are other alternative methods of notification for people who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Another option is the use of televisions in public and working areas with the closed caption feature turned on. The U.S. Department of Agriculture offices in Washington D.C. use this technology.

Is Prior Knowledge of the Circulation Path Location(s) Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once properly notified by appropriate visual notification devices of an alarm or special instructions, people who are deaf or hard of hearing can use any standard means of egress from the building.

Is Identification of Which Means of Egress Are Available/Closest Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people who are deaf or hard of hearing can use any standard means of egress from the building.

Simple floor plans of the building indicating the location of and routes to usable circulation paths should be available in alternative formats such as single-line, high-contrast plans. These plans should be given to visitors when they enter the building so they can find the exits in an emergency. Signs in alternative formats should be posted at the building entrances stating the availability of the floor plans and where to pick them up. Building security personnel, including those staffing the entrances, should be trained in all accessible building evacuation systems and be able to direct anyone to the nearest usable circulation path.

Is Identification of the Path(s) to the Means of Egress Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people who are deaf or hard of hearing can read and follow standard exit and directional signs.

USE OF THE WAY

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people who are deaf or hard of hearing can read and follow standard exit and directional signs and use any standard means of egress from the building.

Elevators are required to have both a telephone and an emergency signaling device. People with hearing or speech impairments should be aware of whether the telephone is limited to voice communications and where the emergency signaling device rings — whether it connects or rings inside the building or to an outside line — and who would be responding to it.

IS ASSISTANCE REQUIRED?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, many people who are deaf or hard of hearing can read and follow standard exit and directional signs and use any standard means of egress from the building. However, some may need assistance in areas of low light or no light where their balance could be affected without visual references.

OCCUPANT NOTIFICATION SYSTEMS

No Special Requirements. People with a speech disability can hear standard alarms and voice announcements and can see visual indicators that warn of danger and the need to evacuate. Therefore, no additional planning or special accommodations for this function are required.

Is Prior Knowledge of the Location of the Means of Egress Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people with a speech disability can use any standard means of egress from the building.

Is Identification of Which Means of Egress Are Available/Closest Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people with a speech disability can use any standard means of egress from the building.

Simple floor plans of the building indicating the location of and routes to usable circulation paths should be available in alternative formats such as single-line, high-contrast plans. These plans should be given to visitors when they enter the building so they can find the exits in an emergency. Signs in alternative formats should be posted at the building entrances stating the availability of the floor plans and where to pick them up. Building security personnel, including those staffing the entrances, should be trained in all accessible building evacuation systems and be able to direct anyone to the nearest usable circulation path.

Is Identification of the Path(s) to the Means of Egress Necessary?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people with a speech disability can read and follow standard exit and directional signs.

USE OF THE WAY

The only standard building egress system that may require the ability to speak in order to evacuate a building is an emergency phone in an elevator. Elevators are required to have both a telephone and an emergency signaling device. People with a speech disability should be aware of whether the telephone is limited to voice communications and where the emergency signaling device rings — whether it connects or rings inside the building or to an outside line — and who would be responding to it.

IS ASSISTANCE REQUIRED?

No Special Requirements. Once notified, people with a speech disability can read and follow standard exit and directional signs and use any standard means of egress from the building. However, some may need assistance with voice communication devices in an elevator.

Chapter 6 BUILDING AN EVACUATION PLAN FOR A PERSON WITH A COGNITIVE DISABILITY

All standard building egress systems require the ability to process and understand information in order to safely evacuate. A cognitive disability prevents a person from using or accessing building features due to an inability to process or understand the information necessary to use the features. These disabilities are caused by a wide range of conditions, but all result in some decreased level of ability to process or understand information or situations.

Possible accommodations for people with cognitive disabilities might include the following:

-

Providing a picture book of drill procedures

-

Color coding fire doors and exit ways

-

Implementing a buddy system

-

Using a job coach for training

OCCUPANT NOTIFICATION SYSTEMS

No Special Requirements. People with cognitive disabilities can hear standard alarms and voice announcements and see visual indicators that warn of danger and the need to evacuate. However, the ability of a person with a cognitive disability to recognize and understand a fire alarm or other emergency notification systems and what they mean should be verified. If the person does not recognize and understand alarms, then plans for assistance need to be developed.

Is Identification of Which Means of Egress Are Available/Closest Necessary?

No Special Requirements. However, the ability of a person with a cognitive disability to find and use the exits should be verified. If the person is not able to recognize and use them without assistance, then plans for assistance need to be developed.

Simple floor plans of the building indicating the location of and routes to usable circulation paths should be available in alternative formats such as single-line, high-contrast plans. These plans should be given to visitors when they enter the building so they can find the exits in an emergency. Signs in alternative formats should be posted at the building entrances stating the availability of the floor plans and where to pick them up. Building security personnel, including those staffing the entrances, should be trained in all accessible building evacuation systems and be able to direct anyone to the nearest usable circulation path.

Is Identification of the Path(s) to the Means of Egress Necessary?

No Special Requirements. However, the ability of a person with a cognitive disability to find and use the exits should be verified. If the person is not able to recognize and use the exits without assistance, then plans for assistance need to be developed.

USE OF THE WAY

No Special Requirements. However, the ability of a person with a cognitive disability to use the exits should be verified. If the person is not able to recognize and use the exits without assistance, then plans for assistance need to be developed.

Who Will Provide the Assistance?

Generally, only one person is necessary to assist a person with a cognitive disability. A practical plan should identify at least two, ideally more, people who are willing and able to provide assistance. Common sense tells us that a specific person may not be available at any given time due to illness, vacation, off-site meetings, and so on. The identification of multiple people who are likely to have different working and traveling schedules provides a much more reliable plan.

Specific Person(s) in the Office or the Building Who:

-

Has special training or skills

-

Is known to the person with the cognitive disability

-

Anyone in the Office or the Building

What Assistance Will the Person(s) Provide?

-

Ensuring that the person with the cognitive disability is aware of the emergency and understands the need to evacuate the building

-

Guidance to and/or through the means of egress

Where Will the Person(s) Start Providing Assistance?

-

From the current location of the person needing assistance

-

From a specific, predetermined location such as:

-

Entry to stairs

-

Other

-

When Will the Person(s) Provide Assistance?

-

Always

-

Only when asked

-

Other

How Will the Person(s) Providing Assistance Be Contacted?

-

Face to face

-

Phone

-

PDA

-

E-mail

-

Visual

-

Other

PERSONAL EMERGENCY EVACUATION CHECKLIST

This checklist is also available as an interactive Microsoft® Word form at http://www.nfpa.org/safety-information/for-consumers/populations/people-with-disabilities. To personalize the form, download it to your local hard drive, then copy and rename the file for each individual for whom an evacuation plan is needed. For advanced instructions, see the Help resources included with Microsoft Word.

Annex A THE ADA: A BEGINNING

The good news is that here in the United States we have developed building codes that have significantly reduced damage and injury to people and property. We have done so well with issues like fire sprinklers, rated construction, and structural stability that we have gone on to the next level and begun to address other issues that are equally important. Energy efficiency, protection of heritage buildings, and accessibility are examples of where we have taken codes beyond traditional requirements.

The bad news is that, while we have made a good start on “accessibility” in the past 55 years, we still have a long way to go. Why does it seem to take so much time and effort to write workable codes and standards for accessibility? What makes dealing with quality-of-life issues, particularly accessibility, so difficult? After all, the goal is simple — we want everyone to have the right to the same opportunities, a right that flows directly from our Constitution. So why are we having such a hard time reaching that goal?

What makes it so difficult is simply that each one of us is unique. We certainly have many general physical features in common, like eyes and ears and organs. But there are differences even in those areas, some small, some great. My eyes are blue, yours are brown, her vision is 20/20, he is blind — there are literally billions of combinations. It’s relatively easy to write code so that we’re all protected in buildings that won’t burn or won’t collapse during an earthquake. It’s much more difficult to make sure that everyone can use a building with equal facility. We now have computer software that can “read” word documents out loud to assist people with visual impairments. We have voice-activated software that can “type” into a computer to assist people with limited use of their hands and fingers. Our goal in accessible code requirements for buildings is to provide that same kind of flexibility and to accommodate anyone and everyone who uses every building.

The first regulations for accessibility adopted in the late 1960s and early 1970s were successful and produced benefits for millions of people. Ramps, elevators, curb cuts, accessible toilets, and signage provided a new freedom for getting to, into, and around thousands of public facilities. Now we’ve learned that those adaptations are only a small part of the solution. We need to address audio and visual accessibility as well as mobility accessibility. What do people do once they’re inside a building? Where do they sit? How good is the quality of those seats? How well can people see and hear? How might they get out of the building in an emergency?

In 1990 Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which is generally considered the flagship piece of legislation on the subject of accessibility. In the act, the term disability means one of the following:

-

A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of a person

-

A record of such an impairment

-

Being regarded as having such an impairment

In developing the ADA, Congress listed the following profound findings:

Some 43,000,000 Americans have one or more physical or mental disabilities, and this number is increasing as the population grows older.

Historically, society has tended to isolate and segregate people with disabilities. Despite some improvements, discrimination against people with disabilities continues to be a serious and pervasive social problem.

Discrimination against people with disabilities persists in the critical areas of employment, housing, public accommodations, education, transportation, communication, recreation, institutionalization, health services, voting, and access to public services. Unlike people who experience discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, religion, or age, those of us who experience discrimination on the basis of disability often have no legal recourse to redress such discrimination.

People with disabilities continually encounter various forms of discrimination, including outright intentional exclusion; the discriminatory effects of architectural, transportation, and communication barriers; overprotective rules and policies; the effects of failure to make modifications to existing facilities and practices; exclusionary qualification standards and criteria; segregation; and relegation to lesser services, programs, activities, benefits, jobs, or other opportunities.

Census data, national polls, and other studies document that people with disabilities, as a group, occupy an inferior status in our society and are severely disadvantaged socially, vocationally, economically, and educationally. People with disabilities have been faced with restrictions and limitations, subjected to a history of purposeful unequal treatment, and relegated to a position of political powerlessness in our society, based on characteristics beyond their control and resulting from stereotypic assumptions not truly indicative of the their abilities to participate in and contribute to society.

The nation's proper goals regarding people with disabilities are to ensure equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for such people. Yet, the continuing existence of unfair and unnecessary discrimination and prejudice denies people with disabilities the opportunity to compete on an equal basis and to pursue those opportunities for which our free society is justifiably famous. This discrimination costs the United States billions of dollars in unnecessary expenses resulting from dependency and non-productivity.

Congress clearly stated its purposes in passing the ADA:

-

To provide a clear and comprehensive national mandate for the elimination of discrimination against people with disabilities

-

To provide clear, strong, consistent, and enforceable standards that address discrimination against people with disabilities

-

To ensure that the federal government plays a central role in enforcing the standards established in the ADA on behalf of people with disabilities

-

To invoke the sweep of congressional authority, including the power to enforce the 14th Amendment and to regulate commerce in order to address the major areas of discrimination that people with disabilities face daily

That clear and powerful message was sent to the American people over 15 years ago, but somehow we missed the point. Somehow we continue to miss the point. Right now, more than 43 million Americans have disabilities. The members of this group are constantly changing — at any moment, you and I could become part of this group for some period of time.

Disability is not about a specific group of people. Disability is about a specific time in the life of each and every one of us. For some it may be temporary, for others it may last much longer.

It’s about the fourth-grader who breaks her leg falling off the playground slide and the hockey player who crashes into the boards 15 seconds into his first college game and is paralyzed from the neck down.

It’s about the construction worker who’s nearly deaf from running a jackhammer and the person born with no arms.

It’s about the 30-year-old asthma sufferer and the 60-year-old office worker recuperating from bypass surgery.

It’s about each and every one of us at some point in our lives.

As a society, we have mistakenly adopted a mindset that divides us into two groups, “able bodied” and “disabled.” The fact is that we all will be part of the disabled community for some time in our lives. It is from that perspective that we need to think about and regulate our built environment and our programs. If we act from the perspective of what we would want when, rather than if, we become disabled, we truly will be able to make great progress for all people.

Annex B GOVERNMENT RESOURCES

This listing of government resources (provided by the U.S. Access Board) may be helpful in developing integrated emergency plans that fully consider the needs of people with disabilities.

A variety of organizations in the public and private sectors provide information on accessibility and accessible design. These links are provided for information purposes only; NFPA and the U.S. Access Board make no warranty, expressed or implied, that the information obtained from these sources is accurate or correct.

ADA Document Portal (http://adata.org/ada-document-portal)

This website, sponsored by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), makes available more than 3,400 documents related to the ADA, including those issued by federal agencies with responsibilities under the law. It also provides extensive document collections on other disability rights laws and issues.

Air Carrier Access Act (http://www.disabilityrightsca.org/pubs/538801.pdf)

The Air Carrier Access Act prohibits discrimination by air carriers on the basis of disability. This act is enforced by the U.S. Department of Transportation, which maintains a hotline for complaints: (202) 366-2220 (voice); (202) 366-0511 (TTY).

Department of Education (http://www.ed.gov)

The U.S. Department of Education funds 10 regional Disability Business Technical Assistance Centers (http://www.adata.org) to provide technical assistance on the ADA. For assistance related to civil rights, contact the department's Office for Civil Rights (OCR) in Washington D.C. (http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/index.html) or the OCR enforcement office serving your state or territory.

Department of Housing and Urban Development (http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/disabilities/sect504faq)

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has issued the Fair Housing Accessibility Guidelines, which cover multifamily housing and are available on HUD’s website (http://www.hud.gov/offices/fheo/disabilities/fhefhag.cfm). Information is also available on how to file a complaint with HUD under the Fair Housing Act (http://www.hud.gov/complaints/housediscrim.cfm). HUD's website also addresses access under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (http://www.hud.gov/offices/fheo/disabilities/504keys.cfm).

Department of Justice's ADA Website (http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/adahom1.htm)

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) website offers technical assistance on the ADA Standards for Accessible Design and other ADA provisions that apply to businesses, nonprofit service agencies, and state and local government programs. It also provides information on how to file ADA-related complaints. Many of its technical assistance letters are available online (http://www.ada.gov/ta-pubs-pg2.htm).

DOJ maintains an ADA hotline: 800-514-0301 (voice); 800-514-0383 (TTY).

Department of Transportation (https://www.transportation.gov/)

(See Federal Transit Administration.)