Health Access for Independent Living (HAIL) Fact Sheet: Working with Your Health Care Provider

Working with Your Health Care Provider

Who Is a Health Care Provider?

When we talk about a health care provider, we are usually referring to a doctor (also called a physician) who has a medical degree. Other health care providers you may interact with often are nurses, nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

This term also includes other health care professionals who provide specific types of care. These providers are dentists, optometrists, pharmacists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech therapists, X-ray technicians, and others.

What Does Working with Your Health Care Provider Mean?

People with disabilities have the same health care needs as those who are nondisabled. They have heart disease, asthma, diabetes and other health issues that may not be related to their disability. Consider Jack’s experience:

Jack is 52 years old and uses a wheelchair. The last few days he’s had a fever and frequent headaches. Yet when he sees his doctor, the physician focuses on his disability rather than his pressing symptoms.

Jack’s example shows us how important it is for people with disabilities to know how to work with their providers. Such scenes are common if the provider has limited exposure to patients with physical disabilities and doesn’t have the skills to build a working relationship with the patient.

“Working with your provider” means building a relationship of mutual trust and respect with your providers. In this give and take, you will advocate for yourself by asking questions and providing information, while your doctor will take your questions and concerns seriously. Your shared goal is your “wellness,” not just “fixing” your problems. In Jack’s case, he probably will remind his doctor that the fever and headaches are not part of his usual experience.

Why Is Working with Your Provider Important?

Of course, people with disabilities do have specific health issues in addition to their general health care needs. Going to a doctor or other health care provider can be a more positive experience when the provider is aware of your unique issues. This information helps providers to meet their patients’ health care needs.

Discuss any specific medical issues that are unique to your disability with your health care providers.

Yet a number of barriers can result in unmet health care needs and poorer overall health. It is important to know that most health care providers do not have much exposure to adult disability in their medical training. So even though they mean well, health care providers may not know how complicated and difficult it is to give good medical services to people with disabilities.

For example, examining a person who lacks sensation in his lower limbs or prescribing medications that adequately address chronic pain can be a challenge for some providers. As a person with a disability, you should discuss any specific medical issues that are unique to your disability with your health care providers.

The key to working with your health care provider is to realize that you are your best advocate. It is vital that you, as a consumer, educate your health care providers on your physical disability and strategies that help you access quality health care. As you help break down barriers and assumptions about people with physical disabilities, you are also helping make access to health care more equal for all.

What Are Your Barriers to Health Care?

You can work with your providers more effectively if you understand what the barriers are in your interactions. Health care is a complex issue for many Americans, especially for people with disabilities. Here are some common obstacles to a satisfying health care visit.

Common barriers to health care for people with physical disabilities include: physical access, provider knowledge and attitudes, poor communication and social policies.

Physical Barriers.

People with disabilities may find it difficult to access their health care provider because of the physical space or architecture of the medical office. This very common barrier includes inaccessible parking, uneven pathways to health care offices, inaccessible medical equipment, narrow doorways, etc. Compensating for physical barriers can drain a lot of time and energy. Physical barriers may also cause patients with disabilities to postpone their visit to the doctor, at the cost of taking care of their health.

Provider knowledge.

As we see in Jack’s story above, a provider’s lack of knowledge is one barrier to accessing health care for patients with physical disabilities. Some doctors might say, “I’m not an expert on spina bifida (or whatever your condition is),” while others are willing to research disability conditions to expand their expertise.

Attitudinal Barriers.

Health care providers may view physical disability as an illness or an abnormality that needs to be “fixed” rather than a natural condition of a person’s life. They may fail to recognize that people with disabilities can be healthy. In addition, when a person with a disability does get sick, some health care providers attribute all of the patient’s symptoms to his or her disability and do not explore new health complaints as thoroughly as they should.

Visits are more effective when health care providers understand that people with disabilities lead full lives with varied interests, are capable of making their own life decisions, and that their disability is not their main preoccupation. Even when a chronic illness is part of a person’s disability, viewing a person as “sick” implies that the person is helpless. This attitude from a health care provider can make a person with a disability feel powerless.

Communication Barriers.

Poor communication between a provider and a person with a disability inhibits accurate diagnosis and treatment. (The limited time that doctors spend during visits is also a barrier.) Sometimes the health care provider talks to a person’s aide or caregiver rather than talking directly to the person with the disability. Or maybe the doctor doesn’t communicate in detail because he assumes that a person who has a physical disability is also incapable of making decisions about a course of treatment.

You can take charge of your health care experience by planning ways to overcome the common barriers.

Social Policy.

Policies that prevent people from having access to comprehensive health care can be a huge barrier. Many people with disabilities are on Medicaid, with limited health care coverage that will not pay for many of their health care needs. As a result, it can be difficult to get necessary medical or dental procedures, assistive technology and proper medications. People with disabilities may then go to the emergency room (ER) instead, which is far more expensive than visiting their primary care doctor regularly. ER visits often stabilize but do not solve a person’s health problems.

How Can You Overcome These Barriers to Work with Your Providers?

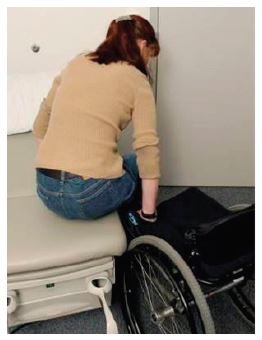

There are many things that a person with a disability can do to improve his or her quality of health care and break down the barriers that compromise care. The following suggestions will help you be in charge of your health care experience. Adjustable height examining tables improve the health care experience for people with physical disabiities [sic]. Providers can get tax credits for this type of equipment.

Physical Barriers

-

Transportation and Access. Prepare yourself. Call your transportation provider and the health care office before your visit if you need to answer the following questions.

-

Will the transportation provider take you directly to the medical office?

-

How long will the driver wait for you if your visit runs over the expected time?

-

Does the building provide easy access to needed rooms, such as lab and X-ray rooms and bathrooms?

-

Are patient instructions and education materials provided in alternate formats if needed, such as large print or audio files?

-

Are the examining and diagnostic rooms user-friendly for your accessibility needs? For example, is there an adjustable height examining table?

-

-

Equipment or aids. Does the health care provider have assistive equipment like wheelchairs, accessible weight scales and other tools that help you have a complete exam?

Attitudinal Barriers

People with disabilities need to be able to recognize health care providers’ unintentional yet unproductive attitudes towards them.

-

Educate your health care provider about your disability and your overall health. Be respectful yet firm in explaining what you know about your own body.

-

Expect respect. If the health care provider is patronizing or disrespectful, address the issue and point out that you would like to be treated just like any other adult patient.

-

Thank your doctor and show appreciation if he or she treats you well. Refer others to that doctor.

-

Choose safety if you feel threatened, frightened, or coerced in any way. If you don’t feel safe, it may be time to change your provider.

-

Explore other providers in your area if you aren’t satisfied. Talk with friends, support groups or your local center for independent living to find a doctor who has experience treating people with disabilities.

Communication Barriers

Effective communication helps to ensure proper diagnosis and treatment. Planning for your visit can improve communication.

Ask if you can bring your aide or a friend to take notes at your doctor visit. Or ask if you can record the visit on your smart phone.

-

Write down all of your questions in order of importance to discuss with your doctor.

-

Ask if you can bring your friend or aide, if you have one, to the appointment with you so he/she can take notes about what’s discussed. Some people like to record a doctor’s visit on their smart phone, but make sure you ask if this is okay. You could say, “I have memory problems, so is it alright if I record our session to listen to later?”

-

Let the doctor know that all communication should be directed to you, even when you have a friend or aide assisting you. This may require a polite request, such as, “Please speak to me instead of her.”

-

Tell the doctor if a certain communication strategy works best for you.

For example, you might need educational materials in an alternate format. Or you could say, “I need information presented in small chunks due to my brain injury. Do you mind speaking more slowly and repeating key points?”

-

Ask if the doctor recommends certain websites that have reliable information about your condition and are written in plain language.

-

Ask questions about follow-up treatment plans, if any, and the expected benefits or side-effects of medications. (See sample questions on our fact sheet “Managing Your Medications.”)

Social Policy Barriers

-

Study your Medicaid/Medicare or private insurance coverage. Learn about which health care services are covered and which are not.

-

Ask your doctor or the person in the office who handles insurance if a recommended treatment is covered by your plan. Also ask how your health care will be compromised by the limitations of Medicaid/Medicare coverage and what you can do about it.

-

Visit your primary care doctor as soon as possible if you are having health issues. Most insurance plans cover preventive visits, and it’s always good practice to find a problem at a more treatable stage. Early detection can prevent complications that might result in a visit to the ER or even a hospital stay.

Resources

-

Physician Experiences Providing Primary Care to People with Disabilities, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2645198/

-

People with Disabilities: What Health Care Professionals Can Do to Be Accessible, http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/documents/pd_hcprof_can_do.pdf

-

Access to Medical Care: Two-DVD Curriculum on Treating People with Disabilities http://wid.org/access-to-health-care/health-access-and-long-term-services/access-to-medical-care-adults-with-physical-disabilities

-

World Health Organization Disability and Health Fact Sheet, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/

-

Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities, http://www.ada.gov/medcare_mobility_ta/medcare_ta.pdf

-

Health Care Access for People with Disabilities, http://www.rtcil.org/products/Healthcareaccess.shtml

-

Information on tax credits for businesses to comply with ADA, http://www.ada.gov/archive/taxpack.pdf

This fact sheet is for informational purposes and is not meant to take the place of health care services you may need. Please see your health care provider about any health concerns.

The contents of this factsheet were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RT5015). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Research and Training Center on Independent LivingThe University of Kansas Rm. 4089,1000 Sunnyside Ave.Lawrence, KS 66045-7561Ph 785-864-4095TTY 785-864-0706 rtcil@ku.edu www.rtcil.org/cl

Project Staff

Jean Ann Summers, PhD

Dot Nary, PhD

Aruna Subramaniam, MS

E (Alice) Zhang, MA

User Comments/Questions

Add Comment/Question