GENERAL NONDISCRIMINATION REQUIREMENTS

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Basic Principles

Equal treatment is a fundamental purpose of the ADA. People with disabilities must not be treated in a different or inferior manner. For example:

- A city museum with an oriental carpet at the front entrance cannot make people who use wheelchairs use the back door out of concern for wear and tear on the carpet, if others are allowed to use the front entrance.

- A public health clinic cannot require an individual with a mental illness to come for check-ups after all other patients have been seen, based on an assumption that this patient’s behavior will be disturbing to other patients.

- A county parks and recreation department cannot require people who are blind or have vision loss to be accompanied by a companion when hiking on a public trail.

The integration of people with disabilities into the mainstream of American life is a fundamental purpose of the ADA. Historically, public entities provided separate programs for people with disabilities and denied them the right to participate in the programs provided to everyone else. The ADA prohibits public entities from isolating, separating, or denying people with disabilities the opportunity to participate in the programs that are offered to others. Programs, activities, and services must be provided to people with disabilities in integrated settings. The ADA neither requires nor prohibits programs specifically for people with disabilities. But, when a public entity offers a special program as an alternative, individuals with disabilities have the right to choose whether to participate in the special program or in the regular program. For example:

- A county parks and recreation department may choose to provide a special swim program for people with arthritis. But it may not deny a person with arthritis the right to swim during pool hours for the general public.

- A state may be violating the ADA’s integration mandate if it relies on segregated sheltered workshops to provide employment services for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities who could participate in integrated alternatives, like integrated supported employment with reasonable modifications; or if it relies on segregated adult care homes for residential services for people with mental illness who could live in integrated settings like scattered-site, permanent supportive housing.

- A city government may offer a program that allows people with disabilities to park for free at accessible metered parking spaces, but the ADA does not require cities to provide such programs.

People with disabilities have to meet the essential eligibility requirements, such as age, income, or educational background, needed to participate in a public program, service, or activity, just like everyone else. The ADA does not entitle them to waivers, exceptions, or preferential treatment. However, a public entity may not impose eligibility criteria that screen out or tend to screen out individuals with disabilities unless the criteria are necessary for the provision of the service, program, or activity being offered. For example:

- A citizen with a disability who is eighteen years of age or older, resides in the jurisdiction, and has registered to vote is “qualified” to vote in general elections.

- A school child with a disability whose family income is above the level allowed for an income-based free lunch program is “not qualified” for the program.

- If an educational background in architecture is a prerequisite to serve on a city board that reviews and approves building plans, a person with a disability who advocates for accessibility but lacks this background does not meet the qualifications to serve on this board.

- Requiring people to show a driver’s license as proof of identity in order to enter a secured government building would unfairly screen out people whose disability prevents them from getting a driver’s license. Staff must accept a state-issued non-driver ID as an alternative.

Rules that are necessary for safe operation of a program, service, or activity are allowed, but they must be based on a current, objective assessment of the actual risk, not on assumptions, stereotypes, or generalizations about people who have disabilities. For example:

- A parks and recreation department may require all participants to pass a swim test in order to participate in an agency-sponsored white-water rafting expedition. This policy is legitimate because of the actual risk of harm to people who would not be able to swim to safety if the raft capsized.

- A rescue squad cannot refuse to transport a person based on the fact that he or she has HIV. This is not legitimate, because transporting a person with HIV does not pose a risk to first responders who use universal precautions.

- A Department of Motor Vehicles may require that all drivers over age 75 pass a road test to renew their driver’s license. It is not acceptable to apply this rule only to drivers with disabilities.

There are two exceptions to these general principles.

1) The ADA allows (and may require - see below) different treatment of a person with a disability in situations where such treatment is necessary in order for a person with a disability to participate in a civic activity. For example, if an elected city council member has a disability that prevents her from attending council meetings in person, delivering papers to her home and allowing her to participate by telephone or videoconferencing would enable her to carry out her duties.

2) There are some situations where it simply is not possible to integrate people with disabilities without fundamentally altering the nature of a program, service, or activity. For example, moving a beach volleyball program into a gymnasium, so a player who uses a wheelchair can participate on a flat surface without sand, would “fundamentally alter” the nature of the game. The ADA does not require changes of this nature.

In some cases, “equal” (identical) treatment is not enough. As explained in the next few sections, the ADA also requires public entities to make certain accommodations in order for people with disabilities to have a fair and equal opportunity to participate in civic programs and activities.

Reasonable Modification of Policies and Procedures

Many routine policies, practices, and procedures are adopted by public entities without thinking about how they might affect people with disabilities. Sometimes a practice that seems neutral makes it difficult or impossible for a person with a disability to participate. In these cases, the ADA requires public entities to make “reasonable modifications” in their usual ways of doing things when necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities. For example:

- A person who uses crutches may have difficulty waiting in a long line to vote or register for college classes. The ADA does not require that the person be moved to the front of the line (although this would be permissible), but staff must provide a chair for him and note where he is in line, so he doesn't lose his place.

- A person who has an intellectual or cognitive disability may need assistance in completing an application for public benefits.

- A public agency that does not allow people to bring food into its facility may need to make an exception for a person who has diabetes and needs to eat frequently to control his glucose level.

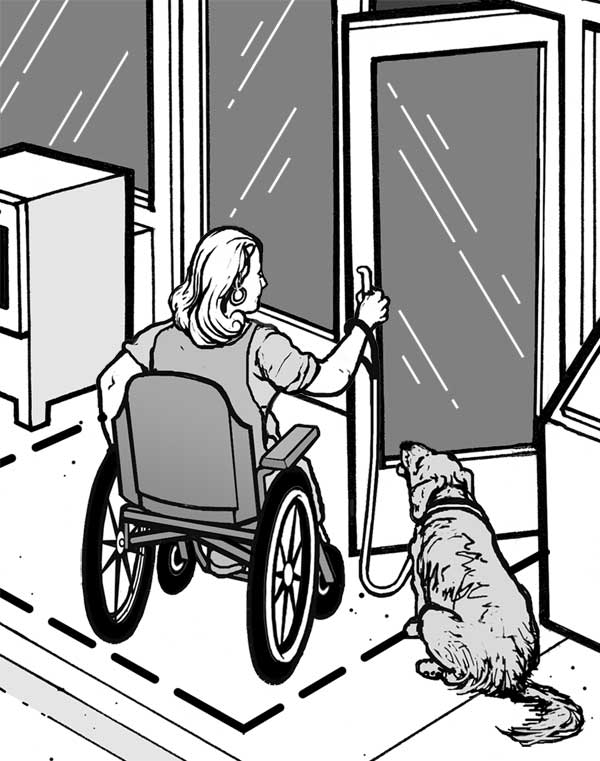

- A city or county ordinance that prohibits animals in public places must be modified to allow people with disabilities who use service animals to access public places. (This topic is discussed more fully later.)

- A city or county ordinance that prohibits motorized devices on public sidewalks must be modified for people with disabilities who use motorized mobility devices that can be used safely on sidewalks. (This topic is discussed more fully later.)

Only "reasonable" modifications are required. When only one staff person is on duty, it may or may not be possible to accommodate a person with a disability at that particular time. The staff person should assess whether he or she can provide the assistance that is needed without jeopardizing the safe operation of the public program or service. Any modification that would result in a "fundamental alteration" -- a change in the essential nature of the entity's programs or services -- is not required. For example:

- At a museum's gift shop, accompanying and assisting a customer who uses a wheelchair may not be reasonable when there is only one person on duty.

- At a hot lunch program for elderly town residents, staff are not obliged to feed a woman with a disability who needs assistance in eating, if it does not provide this service for others. However, the woman should be allowed to bring an attendant to assist her. If she can feed herself but cannot cut large pieces of food into bite-sized pieces, it is reasonable to ask staff to cut up the food.

- If a city requires a 12-foot set-back from the curb in the central business district, it may be reasonable to grant a 3-foot variance for a store wishing to install a ramp at its entrance to meet its ADA obligations. If the set-back is smaller and the ramp would obstruct pedestrian traffic, granting the variance may "fundamentally alter" the purpose of the public sidewalk.

Service Animals

Under the ADA, a service animal is defined as a dog that has been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for an individual with a disability. The task(s) performed by the dog must be directly related to the person’s disability. For example, many people who are blind or have low vision use dogs to guide and assist them with orientation. Many individuals who are deaf use dogs to alert them to sounds. People with mobility disabilities often use dogs to pull their wheelchairs or retrieve items. People with epilepsy may use a dog to warn them of an imminent seizure, and individuals with psychiatric disabilities may use a dog to remind them to take medication. Dogs can also be trained to detect the onset of a seizure or panic attack and to help the person avoid the attack or be safe during the attack. Under the ADA, “comfort,” “therapy,” or “emotional support” animals do not meet the definition of a service animal because they have not been trained to do work or perform a specific task related to a person’s disability.

The ADA does not require service animals to be certified, licensed, or registered as a service animal. Nor are they required to wear service animal vests or patches, or to use a specific type of harness. There are individuals and organizations that sell service animal certification or registration documents to the public. The Department of Justice does not recognize these as proof that the dog is a service animal under the ADA.

Allowing service animals into a “no pet” facility is a common type of reasonable modification necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities. Service animals must be allowed in all areas of a facility where the public is allowed except where the dog’s presence would create a legitimate safety risk (e.g., compromise a sterile environment such as a burn treatment unit) or would fundamentally alter the nature of a public entity’s services (e.g., allowing a service animal into areas of a zoo where animals that are natural predators or prey of dogs are displayed and the dog’s presence would be disruptive). The ADA does not override public health rules that prohibit dogs in swimming pools, but they must be permitted everywhere else.

The ADA requires that service animals be under the control of the handler at all times and be harnessed, leashed, or tethered, unless these devices interfere with the service animal's work or the individual's disability prevents him from using these devices. Individuals who cannot use such devices must maintain control of the animal through voice, signal, or other effective controls.

Public entities may exclude service animals only if 1) the dog is out of control and the handler cannot or does not regain control; or 2) the dog is not housebroken. If a service animal is excluded, the individual must be allowed to enter the facility without the service animal.

Public entities may not require documentation, such as proof that the animal has been certified, trained, or licensed as a service animal, as a condition for entry. In situations where it is not apparent that the dog is a service animal, a public entity may ask only two questions: 1) is the animal required because of a disability? and 2) what work or task has the dog been trained to perform? Public entities may not ask about the nature or extent of an individual's disability.

The ADA does not restrict the breeds of dogs that may be used as service animals. Therefore, a town ordinance that prohibits certain breeds must be modified to allow a person with a disability to use a service animal of a prohibited breed, unless the dog's presence poses a direct threat to the health or safety of others. Public entities have the right to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether use of a particular service animal poses a direct threat, based on that animal's actual behavior or history; they may not, however, exclude a service animal based solely on fears or generalizations about how an animal or particular breed might behave.

For additional information, see ADA 2010 Revised Requirements: Service Animals (PDF)

Wheelchairs and Other Power-Driven Mobility Devices

Allowing mobility devices into a facility is another type of “reasonable modification” necessary to accommodate people who have disabilities.

People with mobility, circulatory, or respiratory disabilities use a variety of devices for mobility. Some use walkers, canes, crutches, or braces while others use manual or power wheelchairs or electric scooters, all of which are primarily designed for use by people with disabilities. Public entities must allow people with disabilities who use these devices into all areas where the public is allowed to go.

Advances in technology have given rise to new power-driven devices that are not necessarily designed specifically for people with disabilities, but are being used by some people with disabilities for mobility. The term “other power-driven mobility devices” is used in the ADA regulations to refer to any mobility device powered by batteries, fuel, or other engines, whether or not they are designed primarily for use by individuals with mobility disabilities, for the purpose of locomotion. Such devices include Segways®, golf cars, and other devices designed to operate in non-pedestrian areas. Public entities must allow individuals with disabilities who use these devices into all areas where the public is allowed to go, unless the entity can demonstrate that the particular type of device cannot be accommodated because of legitimate safety requirements. Such safety requirements must be based on actual risks, not on speculation or stereotypes about a particular class of devices or how individuals will operate them.

Public entities must consider these factors in determining whether to permit other power-driven mobility devices on their premises:

- the type, size, weight, dimensions, and speed of the device;

- the volume of pedestrian traffic (which may vary at different times of the day, week, month, or year);

- the facility's design and operational characteristics, such as its square footage, whether it is indoors or outdoors, the placement of stationary equipment, devices, or furniture, and whether it has storage space for the device if requested by the individual;

- whether legitimate safety standards can be established to permit the safe operation of the device; and

- whether the use of the device creates a substantial risk of serious harm to the environment or natural or cultural resources or poses a conflict with Federal land management laws and regulations.

Using these assessment factors, a public entity may decide, for example, that it can allow devices like Segways® in a facility, but cannot allow the use of golf cars, because the facility's corridors or aisles are not wide enough to accommodate these vehicles. It is likely that many entities will allow the use of Segways® generally, although some may determine that it is necessary to restrict their use during certain hours or particular days when pedestrian traffic is particularly dense. It is also likely that public entities will prohibit the use of combustion-powered devices from all indoor facilities and perhaps some outdoor facilities. Entities are encouraged to develop written policies specifying which power-driven mobility devices will be permitted and where and when they can be used. These policies should be communicated clearly to the public.

Public entities may not ask individuals using such devices about their disability but may ask for a credible assurance that the device is required because of a disability. If the person presents a valid, State-issued disability parking placard or card or a State-issued proof of disability, that must be accepted as credible assurance on its face. If the person does not have this documentation, but states verbally that the device is being used because of a mobility disability, that also must be accepted as credible assurance, unless the person is observed doing something that contradicts the assurance. For example, if a person is observed running and jumping, that may be evidence that contradicts the person's assertion of a mobility disability. However, the fact that a person with a disability is able to walk for some distance does not necessarily contradict a verbal assurance -- many people with mobility disabilities can walk, but need their mobility device for longer distances or uneven terrain. This is particularly true for people who lack stamina, have poor balance, or use mobility devices because of respiratory, cardiac, or neurological disabilities.

For additional information, see ADA 2010 Revised Requirements: Wheelchairs, Mobility Aids, and Other Power-Driven Mobility Devices (PDF).

Communicating with People Who Have Disabilities

Communicating successfully is an essential part of providing service to the public. The ADA requires public entities to take the steps necessary to communicate effectively with people who have disabilities, and uses the term “auxiliary aids and services” to refer to readers, notetakers, sign language interpreters, assistive listening systems and devices, open and closed captioning, text telephones (TTYs), videophones, information provided in large print, Braille, audible, or electronic formats, and other tools for people who have communication disabilities. In addition, the regulations permit the use of newer technologies including real-time captioning (also known as computer-assisted real-time transcription, or CART) in which a transcriber types what is being said at a meeting or event into a computer that projects the words onto a screen; remote CART (which requires an audible feed and a data feed to an off-site transcriber); and video remote interpreting (VRI), a fee-based service that allows public entities that have video conferencing equipment to access a sign language interpreter off-site. Entities that choose to use VRI must comply with specific performance standards set out in the regulations.

Because the nature of communications differs from program to program, the rules allow for flexibility in determining effective communication solutions. The goal is to find a practical solution that fits the circumstances, taking into consideration the nature, length, and complexity of the communication as well as the person’s normal method(s) of communication. What is required to communicate effectively when a person is registering for classes at a public university is very different from what is required to communicate effectively in a court proceeding.

Some simple solutions work in relatively simple and straightforward situations. For example:

- If a person who is deaf is paying a parking ticket at the town clerk's office and has a question, exchanging written notes may be effective.

- If a person who is blind needs a document that is short and straightforward, reading it to him may be effective.

Other solutions may be needed where the information being communicated is more extensive or complex. For example:

- If a person who is deaf is attending a town council meeting, effective communication would likely require a sign language interpreter or real time captioning, depending upon whether the person's primary language is sign language or English.

- If a person who is blind needs a longer document, such as a comprehensive emergency preparedness guide, it may have to be provided in an alternate format such as Braille or electronic disk. People who do not read Braille or have access to a computer may need an audiotaped version of the document.

Public entities are required to give primary consideration to the type of auxiliary aid or service requested by the person with the disability. They must honor that choice, unless they can demonstrate that another equally effective means of communication is available or that the aid or service requested would fundamentally alter the nature of the program, service, or activity or would result in undue financial and administrative burdens. If the choice expressed by the person with a disability would result in an undue burden or a fundamental alteration, the public entity still has an obligation to provide another aid or service that provides effective communication, if possible. The decision that a particular aid or service would result in an undue burden or fundamental alteration must be made by a high level official, no lower than a Department head, and must be accompanied by a written statement of the reasons for reaching that conclusion.

The telecommunications relay service (TRS), reached by calling 7-1-1, is a free nationwide network that uses communications assistants (also called CAs or relay operators) to serve as intermediaries between people who have hearing or speech disabilities who use a text telephone (TTY) or text messaging and people who use standard voice telephones. The communications assistant tells the voice telephone user what the TTY-user is typing and types to the TTY-user what the telephone user is saying. When a person who speaks with difficulty is using a voice telephone, the communications assistant listens and then verbalizes that person's words to the other party. This is called speech-to-speech transliteration.

Video relay service (VRS) is a free, subscriber-based service for people who use sign language and have videophones, smart phones, or computers with video communication capabilities. For outgoing calls, the subscriber contacts the VRS interpreter, who places the call and serves as an intermediary between the subscriber and a person who uses a voice telephone. For incoming calls, the call is automatically routed to the subscriber through the VRS interpreter.

Staff who answer the telephone must accept and treat relay calls just like other calls. The communications assistant or interpreter will explain how the system works.

For additional information, including the performance standards for VRI, see ADA 2010 Revised Requirements: Effective Communication (PDF) .

User Comments/Questions

Add Comment/Question